Hiking Behind the Rocks

By Dave Webb

Posted 1-4-06

Posted 1-4-06

I'm loving this mild mid-winter weather. We've got plenty of snow at the ski resorts and on the snowmobile trails but green grass in the valleys. Some northern Utah golf courses are open and playable. And southern Utah is often sunny, with perfect temperatures for hiking and biking. In my opinion, we couldn't have it better.

During late December the Christmas bustle and a big project at work were significantly cutting into the recreational activities that help me stay sane. I was getting a bit stir crazy and decided I needed a little red rock therapy. I headed to Moab for a few days between Christmas and New Years and had great fun exploring an area known as Behind the Rocks.

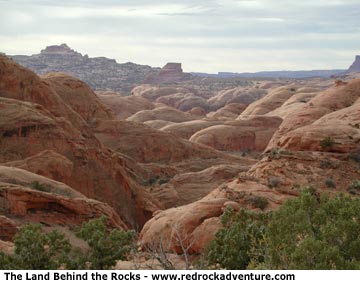

Behind The Rocks is one of Utah's last great unspoiled places, where you can wander to your heart's content. It is located behind the rocky rim southwest of Moab, just a stones throw from town but essentially a million miles away.

Behind The Rocks offers about 50 square miles where there are no trails, no human footprints, no people. You can wander all day without seeing or hearing anything related to humans, except the plumes left by jets high in the sky above.

If you are goal-oriented, intent on hiking to a specific destination, this isn't the place for you. Oh, there are plenty of things to see here - slickrock fins and domes, arches, Indian rock art and ruins, dinosaur tracks - that kind of stuff. But you can't just hike to them. The environment forces you to wander.

Why can't you just hike straight to the neat stuff? No guidebooks, at least that I have found, describe routes to these places. The guidebooks describe what a neat area it is, and give general information about the kinds of things that can be found there, but they don't describe trails to destinations. Perhaps that's because there are no trails. The fins tend to block direct movement through the area, spreading hikers out and inhibiting trail formation.

Why can't you just hike straight to the neat stuff? No guidebooks, at least that I have found, describe routes to these places. The guidebooks describe what a neat area it is, and give general information about the kinds of things that can be found there, but they don't describe trails to destinations. Perhaps that's because there are no trails. The fins tend to block direct movement through the area, spreading hikers out and inhibiting trail formation.

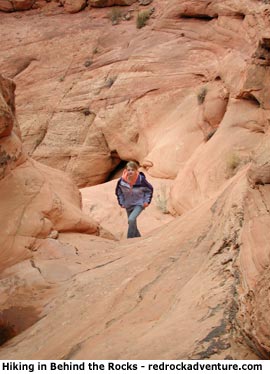

Why is such a scenic, interesting area, so close to civilization, still unspoiled? Because access is extremely difficult. It's darn difficult to get into the area and darn hard to get around once you get in.

If this kind of wild adventure appeals to you then come on, join the Corps of Discovery and start wandering around.

My hike took me through the north portion of Behind the Rocks. The sky was mostly cloudy, the sun breaking through occasionally, and the air temperature was in the upper 40s. Great hiking weather. The absolutely best time to hike here is in early spring and late fall. Summers are very hot with little shade.

You'll have to backpack if you want to explore much of this area, but backpacking is difficult because there are no reliable water sources. There may be a few potholes with water for short times after storms but there are no springs or streams. Rugged canyons cut into the area and water flows through them, 1,000 feet below you, at the bottom of sheer cliffs where it can do you no good.

We hiked in via the Hidden Canyon Trail, which snakes up the rim, crosses Hidden Valley and then ends on the edge of Behind the Rocks. The trailhead is located off US 191 just south of town. A small sign marks the turnoff. I'm not going to attempt to give specific hiking instructions. If you want to explore this area you need a good map, good scrambling skills and the confidence to go it alone.

Three jeep trails approach the area and can be used for access: the Moab Rim Trail on the northeast, the Pritchett Canyon Trail on the west and the Behind the Rocks Trail on the south. I recommend you hike up these trails - don't try to drive them. Even veteran jeepers with modified vehicles hesitate to drive these trails because they are so rough. One guidebook said this about the Pritchett Trail: "As the trail grows tougher vehicles should have at least one locking differential, and drivers should be mentally prepared for the possibility of vehicle damage."

Three jeep trails approach the area and can be used for access: the Moab Rim Trail on the northeast, the Pritchett Canyon Trail on the west and the Behind the Rocks Trail on the south. I recommend you hike up these trails - don't try to drive them. Even veteran jeepers with modified vehicles hesitate to drive these trails because they are so rough. One guidebook said this about the Pritchett Trail: "As the trail grows tougher vehicles should have at least one locking differential, and drivers should be mentally prepared for the possibility of vehicle damage."

An un-national park of arches

Golden Webb provided this description of the Behind the Rocks area:

"It should come as no surprise that one of Utah's most spectacular backcountry destinations is just a stone's throw from Moab. The Behind the Rocks Wilderness Study Area, a compact but rugged region of fins, domes, arches and hidden gardens, lies just outside the town's borders, literally within sight of Moab's main street. Next time you're in the vicinity of that bustling thoroughfare, take a minute and direct your gaze to the southwest. The view breaks on a great red Navajo sandstone wall that bounds the Moab Valley. Hidden beyond its towering facade lies a maze of arches and fins that rival the Devils Garden and Klondike Bluffs of Arches National Park in beauty and surpass those popular tourist attractions in wildness.

"This 1,800-foot precipice marks the eastern terminus of the Land Behind the Rocks, where Arches meets Canyonlands. In the words of local author Fran Barnes the area concentrates the geological and cultural features of Arches and Needles within a "50-square-mile labyrinth of slickrock, fins, domes, arches, giant caverns, sand dunes, deeply cut canyons and lofty rimlands." Roughly 25,000 acres of Navajo sandstone fins rise just beyond the wall that marks the Moab Rim, sheltering narrow, secret gardens that can only be explored on foot.

"Past Pritchett Canyon this unearthly landscape gives way to a region of contorted domes, ledges and small canyons that shed away to the deep chasms of Hunters and Kane Springs canyons. These 400- to 1,000-foot deep, sheer-walled canyons expose perennial springs at the bottom of the Kayenta Formation, dripping seeps and hanging gardens that feed into year-round streams and riparian areas.

"Hidden within this labyrinth of strange and beautiful erosional forms is a concentration of arches similar to that of Arches National Park. Otto Arch, Balcony Arch and Picture Frame Arch are among the 20 major, named rock spans. An additional 20 remain unnamed, and more are discovered every few years. As in Arches, most of the spans have formed in the Navajo and Entrada sandstones. The area is so rugged that one of the largest known arches was not discovered until 1970. Pritchett Arch is perhaps the best known of the rock spans in Behind the Rocks. Resembling Rainbow Bridge in Glen Canyon, this 100-foot-wide, 700-foot-high span was pictured in the February 1910 issue of National Geographic.

"Behind the Rocks was inhabited extensively by the ancient Anasazi and Fremont peoples; evidence suggests that the two cultures overlapped here. Intrepid explorers will discover numerous petroglyph panels, habitation caves, chert-knapping middens (similar to those found in Canyonlands' Indian and Salt creeks) and stone ruins such as the "Indian Fortress," which covers five acres and includes fine rock art and historical inscriptions.

"Scattered amidst the fins and domes are pinyon-juniper forest and brush-dominated parks. The landscape harbors mule deer, coyote, bobcat, cottontail, chukar, cougar and desert bighorn sheep; the cliff faces provide nesting habitat for raptors: red-tailed hawk, great horned owl, prairie falcon, kestrel, and the occasional visiting golden eagle ride the high thermals. Peregrine falcons nest in Hunters Canyon.

"Behind the Rocks offers outstanding hiking, rock climbing and bouldering opportunities. The popularity of the area is increasing, especially among solitude-seeking Moabites. Simple exploratory forays and day hikes are the best option here; backpacking is difficult because of a lack of reliable water sources. The quiet, private stone corridors between the fins are a delight to explore and offer a close look at unique erosional forms. Because there are no established trails within Behind the Rocks, there is a strong sense of exploration as you slip deeper and deeper into its tangled warren of knobs, domes and fins. A person with the time and the means could spend weeks in Behind the Rocks exploring new routes amid real solitude.

"But the very features that make Behind the Rocks so wild and beautiful make it a dangerous place for the unprepared. It's remarkably easy to get swallowed up and lost within the mazes of narrow corridors. Fin canyons often end in pour-offs that require ropework to proceed, and the topography of the land is rough and unforgiving."

Copyright Dave Webb