By Golden Webb

(Published Sept., 2002, Utah Outdoors magazine)

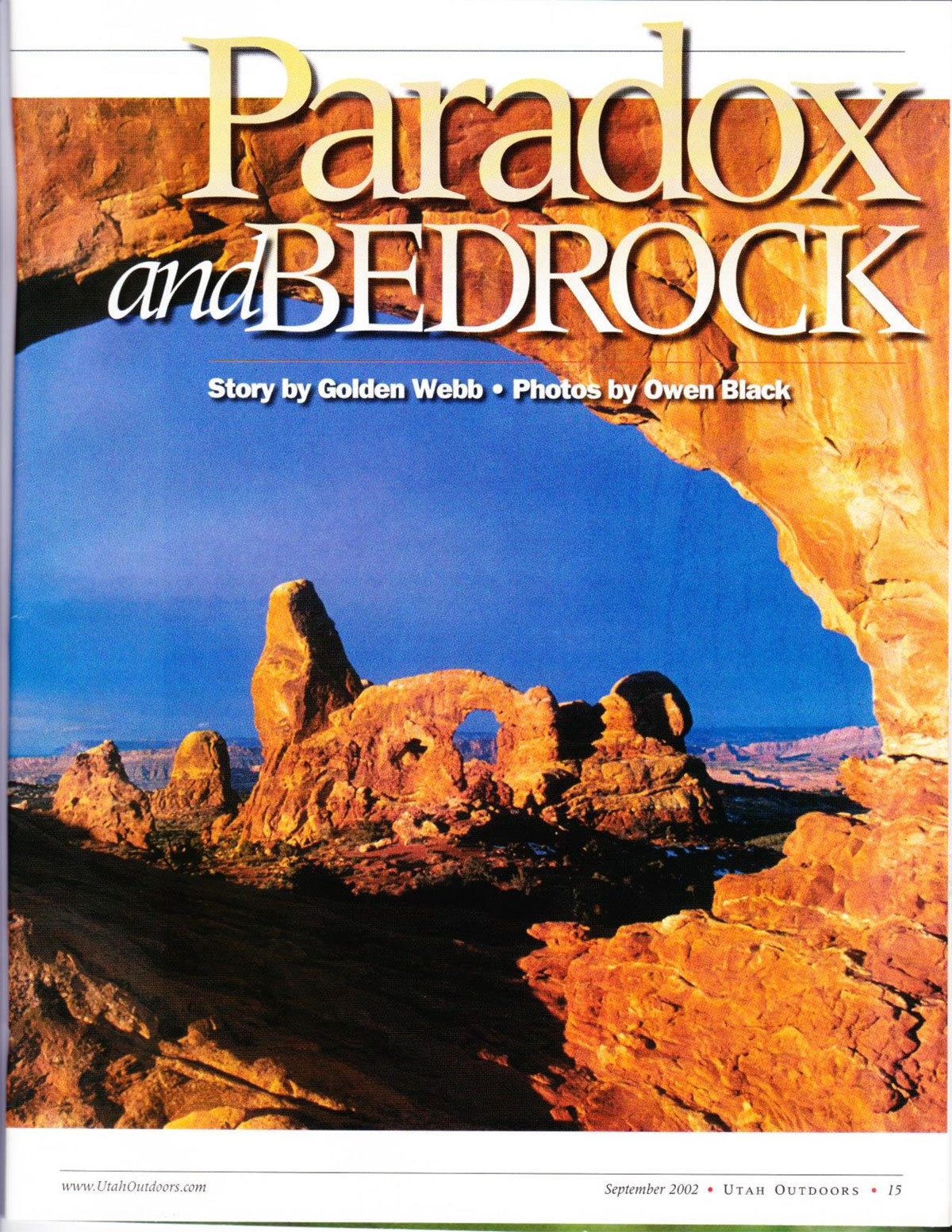

The Four Corners area is full of places that tug at the soul and I’ve seen my share of them—enough now that it’s hard to say anymore whether I favor this or that place over any other. But Arches National Park is something special. It’s a God-haunted place, a Holy Land in the truest sense of the term—the purest, cleanest display of rock and cloud and sky you’ll ever see. Hózhó might be the best word to describe it—Navajo for harmonious beauty.

There are over 2,000 arches concentrated within the park’s 114 square miles. People hear this and yawn. It’s one of those things, like the Grand Canyon or Bo Derek, that’s so extraordinary yet clichéd it’s become prosaic, almost boring. Delicate Arch, blah blah blah, it’s on everyone’s license plate, who cares?

But go look at the thing—really look at it, really see it. More bedrock is exposed on the Colorado Plateau than anywhere else on the continent, and the alchemical mixture of wind and water and time can do amazing things with naked sandstone, but Delicate Arch seems, well, more than that—too perfect, too magical to just chalk up to Bentley’s “fortuitous or casual concourse of atoms.” There’s purpose here, intelligent design—a message in stone from Yahweh, maybe, or some kind of crypto-geological receiver for interstellar transmissions from Betelgeuse.

Or just rock with a hole in it. As Edward Abbey writes:

“There are several ways of looking at Delicate Arch. Depending on your preconceptions you may see the eroded remnants of a sandstone fin, a giant engagement ring cemented in rock, a bow-legged pair of petrified cowboy chaps, a triumphal arch for a procession of angels, an illogical freak, a happening. . . . If Delicate Arch has any significance it lies, I will venture, in the power of the odd and unexpected to startle the senses and surprise the mind out of their ruts of habit, to compel us into a reawakened awareness of the wonderful—that which is full of wonder.”

When you go to Arches don’t be fooled by the names on the signs. South Park Avenue, North Park Avenue, Courthouse Towers, Courthouse Wash—those names don’t fit this place: they’re way too generic, too countrified for these hoodoo voodoo crags, fins, pinnacles and domes. Delicate Arch is as enigmatic and freaky as that monolith on the moon in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Outside Utah they know how to match a name to a place: Atacama, Mojave, Sahara, Kalahari, Gobi, Rub al-Khali, Taklimakan—epic names for epic desert landscapes. Here we have Golden Arches Ronald McDonald National Park, home of Delicate Touch Arch and Tom’s Landscape Arch and Mulching Service.

Not all the names are bad—Dark Angel, for example, is a perfect name for that brooding Mephistophelean pillar that guards Arches’ far northern border. But in a place like this it’s better to cast aside anthropomorphism for the shock of the real. Again, Abbey puts it best:

“The personification of the natural is exactly the tendency I wish to suppress in myself, to eliminate for good. I am here not only to evade for a while the clamor and filth and confusion of the cultural apparatus but also to confront, immediately and directly if it’s possible, the bare bones of existence, the elemental and fundamental, the bedrock which sustains us. I want to be able to look at and into a juniper tree, a piece of quartz, a vulture, a spider, and see it as it is in itself, devoid of all humanly ascribed qualities, anti-Kantian, even the categories of scientific description. To meet God or Medusa face to face, even if it means risking everything human in myself. I dream of a hard and brutal mysticism in which the naked self merges with a non-human world and yet somehow survives still intact, individual, separate. Paradox and bedrock.”

All this quoting of Edward Abbey is unavoidable. Like John Muir and the Sierra Nevada, it’s impossible to separate Arches—or any other place on the Colorado Plateau, but Arches especially—from the bestriding colossus that is the life and legend and writings of Edward Abbey. Arches provided the setting for much of his masterpiece Desert Solitaire—a book that chronicles the three seasons he spent here as a ranger back in the 50’s. Because of Abbey, Arches has both a history and a legend. Be sure and read Desert Solitaire before you come to Arches—or better yet, read it while you’re here.

Most tourists stay on the paved roads between Delicate Arch, the Windows Section, and Devils Garden, leaving the hoodoo-voodoo glories of lesser-known Klondike Bluffs and Herdina Park to a lucky few—mostly people with high-clearance vehicles and 4WD, since the roads to get out there are pretty rough. But it’s worth the trip. The scenery at Klondike Bluffs is comparable to Devil’s Garden but without all the people—Klondike Bluffs gets so few visitors the Park Service doesn’t even keep track of the number. Klondike Bluffs can be accessed via the Salt Valley Road: a sandy, winding track, impassable when wet, that heads west from the main park road approximately 16 miles north of the park entrance. Follow it 7.1 miles until you see a junction with a sign pointing left to Klondike Bluffs. Follow this road 1.5 miles to the Tower Arch Trailhead. Be careful not to take the left turn (which leads to a sandy 4WD road that goes south to Herdina Park) just before the Klondike Bluffs Road.

Herdina Park, a hulking Ayers Rock-like sandstone extrusion that would be cool to visit even without the gaggle of arches hidden away among it’s fins and folds (including Eye of the Whale Arch), can be accessed via the park’s only 4WD road. A ranger warned me to stay off it due to deep sand, but I went anyway and almost got stuck. If you’re up to the challenge, turn left onto the Wilson Flats Road near Balanced Rock; the 4WD road comes in from the north after a few hundred yards (there’s a sign).