|

|

By

Golden Webb

By

Golden Webb

(Published January, 2001, Utah Outdoors magazine)

The sky is blue-black, the air clear, cold — a crystalline winter morning in the southeastern Utah desert. I lay in my bag, warm against the pre-dawn cold that sits down like iron amidst these high plateaus.

After a while I get up and look around. Mist lifts off the rock; midnight-colored ravens wing and caw their way through the misty dawn. Slowly, the desert morning progresses, an unfolding of light, form and texture: blue-lavender dioramas, assuming depth; alpenglow atop the peaks; and then the sunrise spilling over the snowcapped Sierra La Sal, throwing everything into sharp relief.

Soon I’m driving southwest. To my right, through breaks in the rock, I get teasing glimpses, beyond the wall, of a carved uplift of humps, fins, pinnacles and domes, pink-banded, like a battlement atop a stone rampart: the Klondike Bluffs. Unconsciously, my foot presses harder on the pedal.

Klondike

Bluffs is just one of a host of mysterious, seldom-seen areas in and around

Arches that I’ve wanted to visit for a long time. The remote Eagle Park, for

example, located somewhere north of Dark Angel: it’s there on the map, but I’ve

never heard of anyone who’s been there. Or the unnamed region, blank on the

map, that lies southeast of the Petrified Dunes and west of the Big Bend of

the Colorado River — a large, trackless plateau of shifting sand and rolling

slickrock. Then there’s Lost Spring Canyon and its Behemoth Cave, adjacent to

the eroded spine of Devils Garden: Ray Wheeler describes it as an area of “intimate

magic [with] smoothly weathered walls, domes, and alcoves . . .. Emerald groves

of cottonwood contrast with the bare, salmon rock of the canyon.” But it was

Klondike Bluffs, especially the region north of Tower Arch and the Marching

Men, a maze of fins, caves and domes located along the western edge of Salt

Valley, that was most alluring to me. Its white-capped towers are clearly visible

from Highway 191, rising against the backdrop of the Mollie Hogans; but within

sight doesn’t necessarily mean within reach, especially on the Colorado Plateau;

I wondered if I’d ever make it out there.

Klondike

Bluffs is just one of a host of mysterious, seldom-seen areas in and around

Arches that I’ve wanted to visit for a long time. The remote Eagle Park, for

example, located somewhere north of Dark Angel: it’s there on the map, but I’ve

never heard of anyone who’s been there. Or the unnamed region, blank on the

map, that lies southeast of the Petrified Dunes and west of the Big Bend of

the Colorado River — a large, trackless plateau of shifting sand and rolling

slickrock. Then there’s Lost Spring Canyon and its Behemoth Cave, adjacent to

the eroded spine of Devils Garden: Ray Wheeler describes it as an area of “intimate

magic [with] smoothly weathered walls, domes, and alcoves . . .. Emerald groves

of cottonwood contrast with the bare, salmon rock of the canyon.” But it was

Klondike Bluffs, especially the region north of Tower Arch and the Marching

Men, a maze of fins, caves and domes located along the western edge of Salt

Valley, that was most alluring to me. Its white-capped towers are clearly visible

from Highway 191, rising against the backdrop of the Mollie Hogans; but within

sight doesn’t necessarily mean within reach, especially on the Colorado Plateau;

I wondered if I’d ever make it out there.

Accessible by a dirt road, Klondike Bluffs lies on the northwestern boundary of Arches National Park, just beyond the Salt Valley Anticline. Because it’s a bit off the beaten path, Klondike Bluffs receives far fewer visitors than the rest of Arches — ironic, since it served as the original inspiration for special protection of the region.

Arches National Park has been shaped by water, ice, subterranean salt movements — and by lonely, failed men who came to it broken but left spiritually reborn. Men such as the Hungarian-born prospector Alexander Ringhoffer, who, like Edward Abbey 40 years later, came, saw and fell in love. Ringhoffer, the prime mover in establishing Arches as a national preserve, arrived in southeastern Utah to try his luck at mining and prospecting. Exploring Klondike Bluffs in late 1922, he became enthralled by the wild beauty of the place, calling it Devils Garden. With an eye toward making it a tourist attraction, Ringhoffer invited officials from the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad to look the area over. Duly impressed, the railroad man, Frank Wadleigh, wrote to Stephen T. Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, and convinced him to push for the creation of a national monument in the high desert of southeastern Utah. Arches National Monument was created by executive order in 1929; it became a national park in 1971.

The beauties and wonders of Arches owe much to the result of weathering and time upon rock — and to the powerful, glacier-like forces of a substance left behind by ancient seas: salt. Several hundred million years ago the region that now includes Arches was part of the Paradox Basin, a huge, 10,000-square-mile depression; periodically, saltwater seas filled the basin, only to evaporate and leave deposits of salt thousands of feet thick. At the same time that the Paradox Basin was sinking and filling with salt, subsidence from the Uncompaghre Basin to the northeast was overlaying the salt deposits with the rock strata that today makes up Arches’ Entrada sandstone. As these sediments accumulated atop the Paradox salt, the enormous weight caused the underlying salt layers to ooze like ice in a glacier. Over millions of years, these salt deposits, once a mile thick, continuously flowed and buckled, even as more and more sandstone strata buried them under. Today’s Arches National Park landscape, with its fins, pinnacles, fractures and anticlines, reflects the liquid foundation upon which it sits; it has been shaped from both above and below: from above, by wind, ice and rain; and from below, by malleable salt shifting and flowing under the weight of stone.

It’s said that Klondike Bluffs was named for the extremes of cold experienced there. As I climb the snow-frosted Salt Valley Anticline, picking my way up a series of rock steps encased in patinas of ice, a bitter, numbing wind howls along the wall, reminding me just how cold this high desert can get. I climb the wall of the anticline and drop into a hanging valley, a rugged, sandy place surrounded by ribs of rock and knobby towers chiseled from the sandstone. The rock, formed of the slickrock component of Entrada sandstone, is rusty red, like the color of dried blood; on the northern skyline, through gaps in the spires, I can see the white caps of the Moab component atop the wind-burnished ridges.

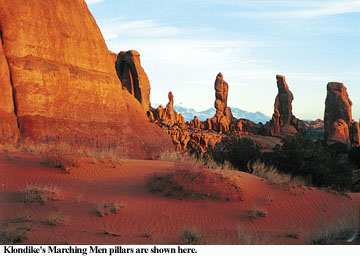

The cairned route leads me to the base of a large orange dune that runs up to a break in a curving, fin-carved wall. To my left rises the serried column of the Marching Men: three pillars atop a fractured spine of slickrock. The dune spills out of a highland of fins and sandstone ridges; once on top, the walls pull close, and I slip between the folds. The place has the feel of an inner sanctum; there’s a hush in the air, a feeling of being watched.

I find myself wondering, a little more than half-seriously, what Edward Abbey wondered once in the Escalante: “Is this at last the locus Dei? There are enough cathedrals and temples and altars here for a Hindu pantheon of divinities. Each time I look up one of the secretive little side canyons I half expect to see not only the cottonwood tree rising over its tiny spring — the leafy god, the desert’s liquid eye — but also a rainbow-colored corona of blazing light, pure spirit, pure being, pure disembodied intelligence, about to speak my name.”

I round a corner, stop. No burning bush, just the last approach before the arch: rolling mounds of pumpkin-orange sand, rippled by the wind; the eldritch, twisted carcass of a dead juniper, reaching clawed hands up toward the winter sun; deep shadows cast by tons of sculptured stone. Up ahead is the hint of an opening-up: a slickrock amphitheater, maybe, and an arch. Beyond that, rugged and forbidding, lie white-capped domes, red-flushed fins, and a maze of intimate slots. I move forward through the sand and shadows.

The Tower Arch Trailhead can be accessed by the Salt Valley Road, a sandy track, impassable when wet, that heads west from Arches’ main road in the vicinity of the Sand Dune Arch turnoff near the Devils Garden Trailhead, approximately16 miles north of the park entrance. Follow the Salt Valley Road 7.1 miles until you see a junction with a sign pointing left to Klondike Bluffs. Follow this road 1.5 miles until it ends at the Tower Arch Trailhead. Be careful not to take the left turn (which leads to a difficult four-wheel-drive road) just before the Klondike Bluffs Road.

Maps: Trails Illustrated Arches National Park; USGS Arches National Park 1:50,000.

Guidebooks: Bill Schneider, Exploring Canyonlands & Arches National Parks, Falcon Publishing; John F. Hoffman, Arches National Park: An Illustrated Guide and History, Western Recreation Publishing.

Arches is racked by extremes of temperature; June through September temperatures may exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit; December through February it can drop below 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Temperatures can range 50 degrees in a 24-hour period! Keep this in mind when planning your trip.

The entrance fee is $10 per vehicle. Devils Garden Campground is located 18 miles from the park entrance and contains 50 tent and trailer sites, and two walk-in group sites (limited to tenting for ten or more persons). The camping fee is $10 per night for individual sites in the summer, $5 per night November through mid-March. Facilities include flush toilets and water until the November frost. You must pre-register for individual tent sites at the Arches National Park Visitors Center between 7:30 and 8 a.m., or at the entrance station (after 8 a.m.). Group campsite reservations are available for two group sites; call (435) 259-4351 for information. The Arches campground fills daily mid-March through October, often by early to mid-morning — get there early and stake your claim. Note: The Devils Garden Campground is closed until February 16 for major water supply line repairs.

Contact information: Phone: (435) 719-2299; e-mail: archinfo@nps.gov ; Web site: www.nps.gov/arch