|

|

By

Alan Peterson

By

Alan Peterson

(Published March, 2000, Utah Outdoors magazine)

The commute to the University of Utah was a regular fixture of my life for several years as I stumbled through the hallowed halls of higher education. For some reason, I have a distinct memory of driving up North Temple on my way to class, listening to a KRSP disc-jockey as he did a Doug Miller outdoor show parody. Who would’ve thought a fish would introduce me to “Mister Twister” himself more than 15 years later.

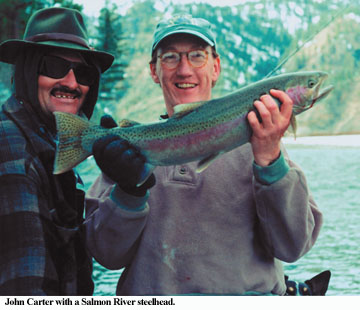

Mister Twister, better known as radio personality Jon Carter, came from Idaho in the late 70’s to KLO. Then, he moved to KRSP, 103.5 FM. It was there over his nine-year tenure that he developed the many characters and radio hi jinx that made him a fixture in Utah’s radio landscape. Having heard a rumor about Carter’s fishing passion, when I saw a picture of him holding a steelhead in a regional magazine I thought it was time for a phone call. I’d heard about steelhead fishing all my life but had never been exposed to it here in Utah. When I asked my dad about it, he said, “All I know is that it’s cold, real cold.”

“It’s gotta be cold, real cold,” proclaims Carter. “They just seem to bite better when it is snowin’ or rainin’.” A professed steelhead addict, he makes several trips each spring and fall to match wits with these sea-going trout. Getting these fish to hit seems half legend-half mysticism but Jon says the weather and water seem to be the controlling factors. 29.9 or lower on the barometer = fish. Any higher...no fish. “Perfect temperature is 33 degrees. Just warm enough so that the ice doesn’t freeze in your guides and a little bit of run-off so that the water is a milky green. Two or three feet of visibility seems to help the bite. Any clearer, the fish scatter at your approach.” Carter continues the laundry list. “Any harder, ‘cardboard box’ color, they can’t see your offering.” With a laugh Carter defines steelheading, “There’s trout fishing, steelheading and then, Idaho steelheading.” Why the passionate difference? The object of Carter’s passion is not just the fish. Deeper runs the passion for the river. The River of No Return. The Salmon River.

The Salmon River is the lifeblood of a one of the few great remaining wild places in the country—one of the last undammed river systems in the US. In fact, the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness Area is the largest designated wilderness area in the continental US. Over 2.3 million acres have been preserved and, at the same time, made accessible. With a network of camps, river routes, trails and back country airstrips, the region has been proclaimed as the best place for family wilderness experiences. The region boasts a large population of mountain lions, bighorn sheep, mountain goat, elk, mule and whitetail deer, moose, marten, fisher, lynx, coyote, red fox, wolverine, and numerous raptors. Additionally, this area is home to a wolf and grizzly reintroduction program. The region’s earliest inhabitants, the Sheepeater Indians, have no known remaining descendants. The town of Salmon is the birthplace of Lewis and Clark guide, Sacajawea. The discovery of gold in Napias Creek in 1866 gave rise to the last large gold rush in the continental US.

The Salmon River is about as close as you can get to Utah and find salmon, other than kokanee. So, if I’m ever going to get the chance to land a steelhead, I need to know this river. It’s obvious I’ve chosen the right guy. Carter’s smooth, radio voice rises a note or two as talks about the river and the fish. That far away look as he describes them let’s you know he’s not discussing generalities. He’s seeing every bend, every turn and reliving every strike as he describes this noted water.

The Upper Salmon isn’t a rough river. From Stanley to about sixty miles downstream from the little town of North Fork, it’s a typical western river. Running two to four feet deep with six or seven foot deep holes behind boulders and logs, with gravel bars that occasionally give way to some runs 25-30 feet deep. Fifteen to twenty yards across, with few rapids above a class II, it’s perfectly suited for a drift boat.

Below “end of the road” where the wilderness area begins in earnest, the river becomes much less benign and is the domain of jet boats. In this, the second deepest river canyon in the States, jet boat and rafting trips are second to none with activities only limited by your imagination. The area is a fisherman’s paradise. From tiny spring creeks with brookies and grayling to the legendary steelhead of the Salmon, and everything in between. Between steelhead strikes you are liable to hook-up with big cutthroat, squawfish, or suckers...big suckers. Recently, Jon hooked into what he thought was the steelhead of a lifetime only to discover it was a ten-pound sucker. Last year, he was surprised by a rare bull trout that weighed six pounds.

When asked about what to expect on a good day of fishing, the answer was, “a good day is none, a better day is one hook-up, maybe one fish and hook-ups count as fish.” One of his best trips with four anglers and four days of fishing was 17 hooked and released with four kept. However, getting skunked is part of the deal. One of Jon’s friends claims that steelhead are a mythological creature because in all his fishing, he’s never seen one. Last year, Jon invited Andrew McKean, the Rocky Mountain editor of Fishing and Hunting News along.

“Not a single fish,” replied Andrew to my call. “Jon is a maniac for the Salmon. But, I haven’t had a strike with him.” Exactly 200 miles from the North Fork store, focal point of the “town” of North Fork, Andrew chooses to spend most of his time farther north on the Clearwater River where the fish are typically larger and more angler friendly. When asked to predict this year’s run, Andrew responded that the fall fish were two months early and that the counting station at Riggins had yet to count a single spring fish. “Significantly smaller fish this year, 28-30 inchers,” he says.

North Fork guide, Ed Link, agrees that size will be down but the numbers of fish are up. He has been catching fish all winter. Milder temperatures and few days with ice in the water have contributed to great fishing. Ed and everyone else now watch for the break-up of the ice jam at Dead Water, a seven-mile long slick that marks the location of the last major ice obstacle to the steelhead’s upriver progress. When the ice breaks, the season is on.

The keys to successful steelheading are three-fold... Location, location, location: The location you fish, the location of your bait, and the location of the fish.

Knowing the river is essential. However much you know, you know nothing compared to the locals. Find one and stick with ‘em. A friend of mine tells of fishing for steelhead all morning in a particularly fishy looking run with no results. After a couple of hours, a local asked him what he was fishing for. My friend wondered if it was a trick question. He carefully said, “Steelhead?” The local quickly responded, “there hasn’t been a steelhead in that run for years. Better move over a few feet.”

Jon’s local expert is long-time friend, Shane Parmer. Jon and Shane met after Jon had spent 10 days on the Clearwater and had caught two fish. Jon was asking around for some local input on the Salmon at a cafe and he was put in touch with “The Clam-man”. That first trip together, they hooked 17 fish. Any wonder they’ve become friends? Shane fixes engines, chops wood, and does the minimum necessary to ensure maximum time on the water as a steelheader. Shane takes his steelheading very seriously, keeping log-books and stats with infinitesimal detail. Shane goes over his records like a day-trader over stock reports. And it pays off. The day I spoke with him, he had hooked five steelhead and landed three.

The name? The secret ingredient of his steelhead weapon, the clam fly. Freshwater clams. Shane forks them up from the Salmon River’s sand bars and banks beginning about August, then keeps them alive for the winter and spring seasons.

The other location factor is getting deep. To a bottom-bouncing bait fisherman, the Salmon is the River of No Refund. “If you’re not losing tackle,” says Carter, “you’re not doing it right.” Remember, these fish are not feeding. You’re not getting them to key on a predominant food source because they’re hungry. When anadromous fish are on the spawn, they don’t feed. Ed Link reports that in all the steelhead he’s cleaned, “they hardly ever have anything in them.” The steelhead in the Salmon will travel 900 miles--one way. And, unlike other salmon species, steelhead don’t die after spawning, they can return to the sea. These fish are exhausted. They are looking for the deepest, slowest holding water they can find. Therefore, learning to read the water is crucial. McKean gives this advice for reading the water: “If the surface looks like crumpled saran wrap, fish it!”

Add to the lack of feeding response, cold water. These fish aren’t looking for any reasons to move from their lies. Once you find them, you have to hit them on the nose. Most of the time, you are annoying them into a strike. Most anglers agree that often steelhead strikes are the fish’s efforts to move an intruder out of their territory. McKean feels that along with reading the water, learning the difference between your bait’s consistent contact with the river bed and the subtle strike of the steelhead is critical. The amount of weight used and the way you are rigged all affect your ability to get your bait to the fish. Unfortunately, reading the water and detecting the strike are not skills you can just pick-up in an afternoon. It takes time and persistence.

Ed Link’s advice is first, stay warm. Waterproof boots and Carhart coveralls. Second, location. The locals know where the fish are. Finally, patience. Fish an area thoroughly before you move on.

All steelhead anglers agree, persistence has no substitute. Terry Leuzinger, owner of Terry’s Sport Shop in Challis, is a four season steelheader and has taken persistence to a new level. During the winter months while fishing the ice ledges on the Salmon, Terry will locate a fish or hole, scrape a mark on the ice with his boot and then works a jig twenty times over the fish, literally knocking them on the nose. Rubber-tail smallmouth-style jigs are better than deer hair or marabou because they don’t ice up as easily. If he gets no response, he moves five feet either side of his mark and starts again. Consistent persistence.

More traditional approaches include heavy gear. Level-wind bait casting reels loaded with 12-14 lb mono. Carter prefers Trilene fluorescent green XL and an AbuGarcia Ambassadeurr 5500-C3, level wind bait caster. Rods should be medium to fast action and 8 1/2 to 9 feet in length. Carter’s favorite is an 8 1/2 foot, GLoomis GL2. Open faced spinning combinations can also be used. Just remember, if you’re going to err, do it on the heavy side. You don’t need a lot of line. 150-200 yards is plenty. After two or three runs they’ll be ready for the net unless they get into the main current. But, make sure your drag is set correctly. Don’t let them take off with everything on that first run. These fish have traveled a long, long way. It is a rare fish indeed that takes you to the bare spool. As for fight, it varies with each fish.

Two of Jon’s experiences illustrate the wide variation. Two springs ago, at a place called Dead Man’s Hole (a name that could only have come from a fisherman or a cattle rustler), with a cold front moving in, Jon hooked a 28-incher (a baby by steelhead standards) that nearly ripped his arms off and lead him on a merry chase. Shortly after that, however, a fisherman on a high bank indicated he could see a large fish in an area Jon and his wife, Cidney, might be able to reach. The fisherman directed them in, Cidney made a three foot cast, and hooked into a 38 1/2 inch fish that was in the boat in less than two minutes.

As for technique, they are as varied as the fishermen themselves. But it’s basically a drift fishery. Bait fishing is done with corkies, spin-glows, pencil weights and bait (sucker meat, shrimp, cottonwood grubs, clam).

Shane’s

infamous clam fly rig is as follows: Secure a three-way swivel with your green

Trilene XL from one of the two in-line eyes. Next, push a four-inch piece of

surgical tubing over the eye that would be the attachment point for a dropper.

Secure it with a wrap or two of fine wire and then roll the collar of surgical

tubing down over the wire. Your pencil lead weight will slide into the surgical

tubing. Tie an 8 to 12-inch piece of clear mono to the remaining terminal eye

of the swivel in line with your green XL. The clear mono should be a couple

of pounds lighter than the XL. You’re going to spend a lot of time snagged and

it is better to lose half your rig as opposed to all of it. A round, green corky

is run on the clear mono followed by a winged spin-glow in glow-in-the-dark

green (not easy to find). Next slide on a couple of colored plastic beads and

then tie on your # 10 bait hook. Attach a couple of two-inch pieces of flourescent

yarn to the hook shaft. These will be used to secure the clam strip once it

is threaded on the hook.

Shane’s

infamous clam fly rig is as follows: Secure a three-way swivel with your green

Trilene XL from one of the two in-line eyes. Next, push a four-inch piece of

surgical tubing over the eye that would be the attachment point for a dropper.

Secure it with a wrap or two of fine wire and then roll the collar of surgical

tubing down over the wire. Your pencil lead weight will slide into the surgical

tubing. Tie an 8 to 12-inch piece of clear mono to the remaining terminal eye

of the swivel in line with your green XL. The clear mono should be a couple

of pounds lighter than the XL. You’re going to spend a lot of time snagged and

it is better to lose half your rig as opposed to all of it. A round, green corky

is run on the clear mono followed by a winged spin-glow in glow-in-the-dark

green (not easy to find). Next slide on a couple of colored plastic beads and

then tie on your # 10 bait hook. Attach a couple of two-inch pieces of flourescent

yarn to the hook shaft. These will be used to secure the clam strip once it

is threaded on the hook.

That’s it. Cast up and across and let it drift right along the bottom. Or, drift your boat through a likely holding area, row back up and drift it again. Repeat...a lot. During the winter, when ice is in the water, try suspending your bait under a bobber. Winter is the time to try jigging as well. Tip your jig with an offering of the above mentioned baits. Remember, the takes will not be big and aggressive.

When asked for the most important thing to remember about fishing the clam fly, Shane laughed, “if you don’t catch ‘em, I will.”

Hot-shotting may be the quickest way to catch fish, according to McKean. Hot-shotting requires a diving lure, something with a big lip that can get down fast or a flatfish-style lure. It’s essentially reverse trolling. The anglers stand in the front of the boat while the oarsman back-rows to slow the boat below the speed of the current. This allows the lure to pull against the current and dig deep. As the boat moves downstream, the lure digs and bounces it’s way along the bottom slowly scraping downstream. If you see your line go slack, or move one way or the other, set the hook. Carter describes these fish as very hard-mouthed, “they should be called steelmouth.” Use heavy, sharp hooks (Jon likes Gamakatsu) and really rear back. Steelhead are not solitary travelers. If you catch one, keep working the same area. You’re likely to catch others.

Steelhead are rainbow trout that have been hatched in fresh water and lived one year to eighteen months slowly traveling down river as fry. The smolt stage is reached as they make the change to live in salt water. Once they make it to the ocean they spend roughly one to three years in the salt and then, through one of nature’s true wonders, return to the very place they hatched to spawn and start the whole process over. Shane is a wealth of information on the Salmon River run, the longest migration of any fish in the world.

Steelhead leave the salt water and enter the mouth of the Columbia in April and begin their incredible journey. Water temperature determines rate of travel. At 38-42 degrees, steelhead can travel 7 to 10 miles per day. At 32-35 degrees, their speed slows to only one or two miles per day. By September, the first fish will be reaching the Salmon area. By November, they will have finished. However, when fish enter the Columbia late, or are slowed by any one of innumerable obstacles, the cold water of December and January slows them down. These “lay overs” produce what is often regarded as a second run February through April.

The salmon are divided into an A-run and B-run classification. A-run fish are genetically different in that they are smaller, running 20-28 inches. B-run genes push steelhead to 28-42 inches. “Over 40 inches is a killer-B.” B-run fish are characteristic of the Yakima, Clearwater, Lower Snake, and Little Salmon. Fishing closes down after April 30th to protect the remaining wild fish that migrate much later than the hatchery fish. Ninety percent of the wild B-run steelhead in the Salmon arrive late and seek out the Middle Fork to spawn. “Out of 100 fish that I’ll boat, only five will be wild,” says Shane. “And they all go back into the river.” All hatchery fish are recognized by their clipped adipose fin. “Without the hatcheries, we wouldn’t have a fishery.”

In the late sixties and early seventies, the US government completed a series of dams on the Columbia and Snake creating a huge transportation and irrigation system that made Lewiston, Idaho, nearly 500 miles from the Pacific, the West Coast’s inland most seaport. Fearing an effect on the fish stocks, the legislation that created the dams also created hatcheries and methods of getting the fish around the dams. In fact, more the $3 billion dollars have been spent in the effort. However, the toll on the salmon stocks has been devastating. Every species of salmon and steelhead in the Snake River (the Salmon is it’s main tributary) is now listed under the Endangered Species Act.

According to Idaho Department of Fish and Game’s numbers (quoted in a fascinating New York Times article by Sam Howe Verhovek, September 26th, 1999), last year’s count was: 8,426 spring and summer run chinook, 306 fall chinook and 2 sockeye. The river’s coho salmon have been declared extinct. Steelhead numbers in 1997 were half of what they were in 1987. But the cyclical return of the salmonids has allowed hatcheries to maintain a hope of recreating the fishery. This mysterious return has been both the salmon’s salvation and it’s undoing. Oddly enough, the billions spent on fish ladders and other technologies that help the salmon go upstream miss the fact that it’s the trip down river that is the key to the salmon’s return.

The only way for a salmon to get passed the dams on the down river trip is to go over a spillway or through the hydroelectric generating turbines. Put a six-inch fingerling in your blender and you’ll get an idea of a salmon’s chances in the turbines. The Government has tried trucking and barging the salmon around the dams to little effect. In fact, the mortality rate for the millions of young salmon, wild or hatchery reared, is close to 96%. This is one of the reasons steelhead, though endangered, can be harvested. They can make the trip, sea to redd, numerous times but, if they do survive the arduous journey home the first time, they are doomed when they turn around and head down river.

Idaho Fish and Game’s chief biologists have testified before Congress that the most important action that can be taken to restore salmon stocks is to remove the dams. Cecile Andrus, the governors of Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and Idaho have, over the past three years, all lent support to the concept of removing the dams. 107 members of congress have done so as well. But, built around the agricultural, hydroelectric and transportation success of the dams are the lives of tens of thousands of individuals and families, businesses and farms depending for their livelihood on those dams.

The fate of the dams is a highly controversial subject and one that Utahns should watch with great interest. Within the last year, voices calling for the removal of Glen Canyon and Flaming Gorge dams have made themselves heard. What happens to the Columbia/Snake dams may be the auger of the future for our own backyard. As seen years ago when a little fish called a snail darter changed the course of US policy, again a fish, oblivious to all but it’s own goings and comings, takes center stage both politically and in the hearts of it’s passionate devotees (for more information on the status of salmon and the dam debate, see side bar).

Shane Parmer is adamant. “Most of the power goes out of the country, the water on the high desert grows apples that get shipped out of the country. We just want to keep the fish here.” Carter is practical about the debate. “I don’t know,” he says with a thoughtful look. “There are good years and bad years. But we still catch fish. We keep coming back.” With luck, so will the steelhead.

North Fork Store: 208-865-2412. A campground, motel, cafe, liquor store, post office, grocery and tackle shop, and US Forest Service District Rangers Office all with a few feet of each other...that’s how to design a town.

North Fork Guide Service: Contact Ed Link 208-865-2520

Terry’s Sport Shop, Challis, Idaho: Contact Terry Leuzinger 208-879-2500

Anglers’ Inn, contact Terry Peterson: 801 466 3921. (Our home town boys can easily set you up for steelheadin’... Idaho steelheadin’.)

Fish counts. Yearly fish counts, some going back to 1910. If you’re planning a trip, you can look at a 10-year history and know on what days, how many fish were in the system and make a guess as to when you should go. www.cqs.washington.edu/dart/help

Bob’s Piscatorial Pursuits. Lots of great informtion from terminal tackle to salmon recipes. Though focusing on Washington/Alaska fishing, the information applies to Idaho fish as well. www.piscatorialpursuits.com

Onother site worth visiting: The Steelhead Site, http://steelheadsite.com

New York Times Articles: www.nytimes.com/library/national/science/100599sci-animal-salmon.html

National Marine Fisheries Service, North West Region: www.nwr.noaa.gov/1salmon/salmesa/index.htm

Columbia and Snake Rivers Campaign: www.removedams.org

Idaho Steelhead & Salmon Unlimited: www.idfishnhunt.com/issu.html

Idaho State Fish and Game: www.state.id.us/fishgame

US Forest Service: 208 839 2211

Idaho Fish ‘n’ Hunt: www.idfishnhunt.com

Ask Fish (fishing reports) 1-800-ASK-FISH

Salmon River Chamber of Commerce: 208 628 3778 or, www.rigginsidaho.com

Idaho River Flow Information (Mar.-Oct.) 1-208-327-7865