Drive The Burr Trail

The Most Scenic Backroad of them All

Text

and photos by Golden Webb

Text

and photos by Golden Webb

I’d awakened that morning to winter smog. Not a cool wet fog on little cat feet, but one of the Wasatch Front’s patented black-smoggy-death-clouds, the kind that kills stray dogs. No matter. Smog like that gives me an excuse to flee to the Elysian graces of the desert, where the air smells like sagebrush instead of car exhaust, where the only particulates in the air are empty husks of locusts and fine clean granules of blowsand.

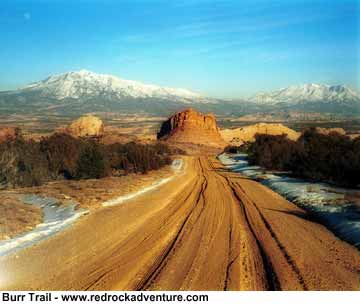

I headed south on I-15 in my Chevy truck, traveling at first without a destination in mind, only a direction. I was hungry for beauty but only had a day to find it. I needed a superlative road to explore–one of Utah’s beautiful backways. Almost unconsciously I found myself angling southeast across the state, following some kind of inner homing impulse like a wistful pigeon toward the Burr Trail–the most beautiful backroad of them all. An officially designated "National Scenic Backway," the Burr Trail is a partially paved route that connects Highway 12 in the town of Boulder with Bullfrog Marina on Lake Powell. Beginning in the foothills of the Aquarius Plateau, it winds down through spectacular backcountry areas of Grand Staircase-Escalante NM, Capitol Reef NP, and Glen Canyon NRA, passing through a remarkable quilted patchwork of federally protected lands and proposed wilderness areas.

Cloistered

for decades by its remoteness and rugged topography, until recently the

Burr Trail was a hard place to explore, one of those rare 70+-mile roads

in the Lower 48 where a high-clearance (and, in some cases, four-wheel

drive) vehicle was essential to see much of its length. That changed in

the 90s, when all but the 16 miles of road within Capitol Reef was paved

by the BLM. Aside from a few environmentalists (whose delicate esthetic

preferences were bruised), most people have welcomed this increased accessibility.

The Burr Trail now offers something for both the casual automobile sightseer

and the hardcore explorer. The road takes the car-bound into some of Utah's

most beautiful and extraordinary country, offering glorious views from

every direction; it also offers canyoneers and hikers backcountry access

to the wild-and-woolly Eastern Escalante Drainage, one of the world’s

most spectacular canyon systems, and to the Waterpocket Fold, with its

little-explored slots and high slickrock ramparts.

Cloistered

for decades by its remoteness and rugged topography, until recently the

Burr Trail was a hard place to explore, one of those rare 70+-mile roads

in the Lower 48 where a high-clearance (and, in some cases, four-wheel

drive) vehicle was essential to see much of its length. That changed in

the 90s, when all but the 16 miles of road within Capitol Reef was paved

by the BLM. Aside from a few environmentalists (whose delicate esthetic

preferences were bruised), most people have welcomed this increased accessibility.

The Burr Trail now offers something for both the casual automobile sightseer

and the hardcore explorer. The road takes the car-bound into some of Utah's

most beautiful and extraordinary country, offering glorious views from

every direction; it also offers canyoneers and hikers backcountry access

to the wild-and-woolly Eastern Escalante Drainage, one of the world’s

most spectacular canyon systems, and to the Waterpocket Fold, with its

little-explored slots and high slickrock ramparts.

Sadly, I don’t have time on this trip to get out and roam on my feet; I plan on seeing what I can from my truck. I drive eastward out of Boulder on shiny new chip-sealed asphalt, past bucolic green fields and white checkerboard Navajo Sandstone domes. Stately ponderosa pines tower over dry sandy washes. Off to the northwest the snow-bound bulk of the Aquarius Plateau pushes into the clear January sky.

The road wraps around a cliff and swings south, plunging down to the dancing waters of The Gulch. One of Grand Staircase-Escalante’s most popular canyons due to its easy walking and glorious scenery, in the winter The Gulch exhibits a spare sylvan beauty: leafless cottonwood groves rise above silvery sage and a muddy stream. The place seems completely abandoned. Not a single solitary soul in sight–no cars at the trailhead, no other cars on the road, not even an airplane in the sky. The empty road means only one thing: emptier backcountry. Oh the humanity! Equipped with more time I could have had The Gulch all to my greedy little iconoclastic self–surely a rare opportunity.

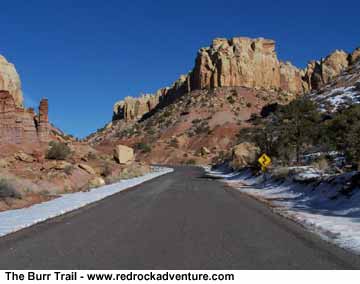

Instead, and with deep regret, I drive right on by. I cross over a concrete bridge and enter the Stygian corridor of Long Canyon. Soaring Wingate cliff faces cast long cold shadows across the road even though it’s midday. The canyon floor on either side of the road is buried in rolling slopes of fallen riprap and scree; massive sandstone blocks and boulders stand balanced at the angle of repose, waiting patiently for an earthquake. Pinyon pines, twisted junipers, and tall ponderosas grow in unlikely places out of the rocky detritus. There are so many interesting things to look at; the canyon could almost be an open-air art gallery, except that everything’s a wild, chaotic jumble. The only regularity in the scene is the mostly-straight road, which I follow until it tops out in the heights of the Circle Cliffs Upwarp.

The canyon walls fall away and the horizon leaps back several miles. I pull over at a scenic overlook, hop out of the truck. The sky above my head is 360 degrees of blue; at approximately 6,600 feet in elevation, the air has a good clean bite to it. The overlook breaks on an expansive view of the Circle Cliffs: inward-facing Wingate ramparts that encircle a huge basin of rust-colored badlands and pinyon-juniper woodland. Patterns in the landscape carry the eye past castellated cliffs to distant white peaks on the eastern skyline–the Henry Mountains, the last-surveyed and last-named mountain range in the continental United States.

Wild

country. I can’t wait to get down into it.

Wild

country. I can’t wait to get down into it.

I turn to get back in my truck. A huge jackrabbit spooks from a scatter of junipers in an explosion of movement and sound. I recoil in terror. The jackrabbit bounds in a panicked zigzag back into the orange mouth of Long Canyon: a blur of white and a puff of dust, then stillness. Everything is as it was before–except my pride. "Mangy rabbit," I say as I climb into the cab. Actually, not a rabbit at all but a hare–or, in Edward Abbey’s more precise terminology, a "black-tailed mule-eared wall-eyed lagomorph." I make a silent promise to come back here with a .22 and go rabbit hunting.

I drop into the Circle Cliffs amphitheater and race across its vast basin. A bug glances off the windshield, leaving a pastel smear on the glass at eye level. I can’t understand how a bug could be flying around down here in January, but there it is. I pass through the Studhorse Peaks (named after the stud horses that stood vigil on the high ground here, guarding their mares) and descend to the entrance of Capitol Reef National Park. Here the pavement ends abruptly, the velvety smooth macadam giving way to slick gumbo mud.

My truck slews in the deep moist ruts; sticky wet clay thumps in the wheel wells. This is the Burr Trail as it was 30 years ago–well nigh impassable. I shift into 4WD High and slalom along for a few miles toward a break in the slickrock mass of the Waterpocket Fold. I splash through a half-foot of flowing water where the road follows the course of a (usually dry) streambed, pass through the seam in the cliffs, and pull off the road at the top of the infamous Burr Canyon switchbacks. A century and a half ago these switchbacks were the crux of the cattle trail built by John Atlantic Burr, a rancher who moved his herds back and forth between the Aquarius Plateau and Bullfrog Basin on the Colorado River.

If Burr’s ghost lurks in this country, I’m sure it often stops at this high desert perch to admire the beauty. The air up here is thick with the distilled magical essence of the Burr Trail; if I could bottle it up somehow and sell it to the Japanese, I’d be richer than a Rockefeller. To the east, honey-colored cliffs frame a phantasmagoric panorama of eroded mesas and snowy mountains. To my right and left the Fold’s knobby ridgeline extends into the wings, the devil’s very own backbone pointing south toward Lake Powell and north toward Thousand Lake Mountain. Below my feet the road drops in a series of vertiginous Z’s into the cool shadows of Burr Canyon.

It’s too much to take in all at once. I mentally slice the scene up into frames and savor each one individually: The Fold’s Navajo sandstone glowing in the rich afternoon sunlight; the bruise-gray badland hills spilling off the crumbling rim of Swap Mesa; the laccolithic cones of Mount Pennell and Mount Hillers floating above the desert flats, their shimmering, snow-clad slopes white as sun-bleached bone.

Gorgeous, stunning, wild country.

As I climb back in the truck, a snippet of verse pops into my head: "I like a road that leads away to prospects bright and fair, a road that is an ordered road, like a nun’s evening prayer; but best of all I love a road that leads to God knows where." Another poet, Shakespeare, said, "All roads lead to Rome." In Utah’s desert country, all backroads lead to adventure and discovery. I shift into 4WD Low, point my Chevy down the switchbacks, and continue my journey on the most beautiful backroad of them all, sinking deeper into its matrix of geology, history, and raw beauty.

If You Go

Warning: Though open year-round, the Burr Trail is still a fair weather road. Although in dry weather it is easily accessible to passenger cars, wet weather may make the road impassable even for 4WD vehicles–especially the unpaved section through Capitol Reef. Southern Utah has been pounded by storm after storm this winter. Check with rangers or local officials for weather and road conditions.

Drive Time (in good weather): 2-3 hours.

Elevation: 3,900-6,600 feet.

Access: The Burr Trail can be accessed either from Utah 12 in the town of Boulder or from Highway 276 five miles north of Bullfrog Marina.

Current Road Information: Capitol Reef National Park, HC-70 Box 15, Torrey, UT 84775, (435) 425-3791; or Escalante Interagency Office, 755 West Main, Escalante, UT 84726, (435) 826-5499.

Maps:

BLM: Hite Crossing, Escalante

USGS: 1:24,000 Bull Frog, Hall Mesa, Clay

Point, Deer Point

1:100,000 Hite Crossing, Escalante

Maptech CD-ROM: Moab/Canyonlands; Escalante/Dixie

National Forest

Trails Illustrated,

#213

Utah Atlas & Gazeteer, pp. 28,

20, 21

Copyright Golden Webb