By Larry Tullis

By Larry Tullis

(Published Feb. 1995, Utah Fishing & Outdoors)

Although the midge is often ignored by fly fishermen, it seldom is by the trout. Because of their prolific nature midges are a

valuable food source for trout, but because they are so small, the fish must eat lots of them. This gives the midge fisherman, who takes the time to learn to fish the midge properly, many chances to catch midge-feeding fish.

Midges on the Green River

A recent trip to the Green River showed me just how valuable the midge is to trout. When I arrived, the fish were already feeding on a good midge hatch. I had rigged up with two small nymphs anticipating sluggish fish on the bottom because

the water temperature was below 40 degrees Fahrenheit. Instead, the winter midge hatch was in full bloom and fish were stacked along the slower current edges devouring the plentiful midges as they worked to free themselves from the water.

Since I was rigged up for nymphing, I tied a midge larva to the end and fished it dead drift along the current seam. I quickly hooked a couple of fish. A stomach pump sample of one fish showed that he was feeding heavily on midges. There were a

few scuds and an aquatic worm in the sample but midge larva dominated about 50 to 1 over other foods. The hatch was primarily a yellow-brown colored midge but there were a few red midge larva mixed in.

After catching a couple more fish, things slowed down considerably. It quickly became apparent that the fish were feeding heavily on the midge adults and were now ignoring the deep running nymphs I was presenting.

I quickly changed to a dry fly strike indicator and put a trailing emerger pattern about 30 inches behind the indicator. The greased emerger floated in or near the surface but could not be seen. When a fish rose near the larger attractor, I automatically set the hook and would often be hooked into a trout.

The larger dry fly allowed me to track the smaller fly fairly closely even though I could not see it at all.

The hatch progressed to where most of the insects available were adults. A Griffith’s Gnat proved to be a good pattern when fished on a light tippet. Later I tried a very small Thorax Dun pattern that was close enough to the midge’s shape and size to be effective and it was easier to see than the Griffith’s Gnat. The fish were very selective, but would fall for each of the flies

mentioned when drifted properly over a feeding fish.

Between midge hatches that day, I tried other nymphs with little success. If I had not been prepared with midge patterns, I would not have done well at all. As it turned out, I had a ball challenging my skill against the selective fish.

A midge’s life cycle

As the Green River example showed, imitating the various stages of the midge hatch was important to consistent success. Knowing about the foods that trout eat is important if you want to catch fish consistently wherever you fish.

The midge is a member of the Diptera Family which includes midges, craneflies, deerflies, gnats and mosquitos. The adults look similar to mosquitoes (however midges do not bite) but midges have wings that are generally shorter than their body. Mosquitos generally have wings longer than their bodies. Many midge-like insects are actually small craneflies but it is not important for the angler to be able to tell them apart because the same fly pattern can be used to imitate both.

Even though the midge is very small (imitations range from size 16 to 26), the midge is very important to trout because of the incredible number of individuals that hatch, especially in the winter when the midge is often the only active insect

that is available to the trout regularly. On many waters midges hatch every day of the year and individual species may have 2 or more life cycles per year.

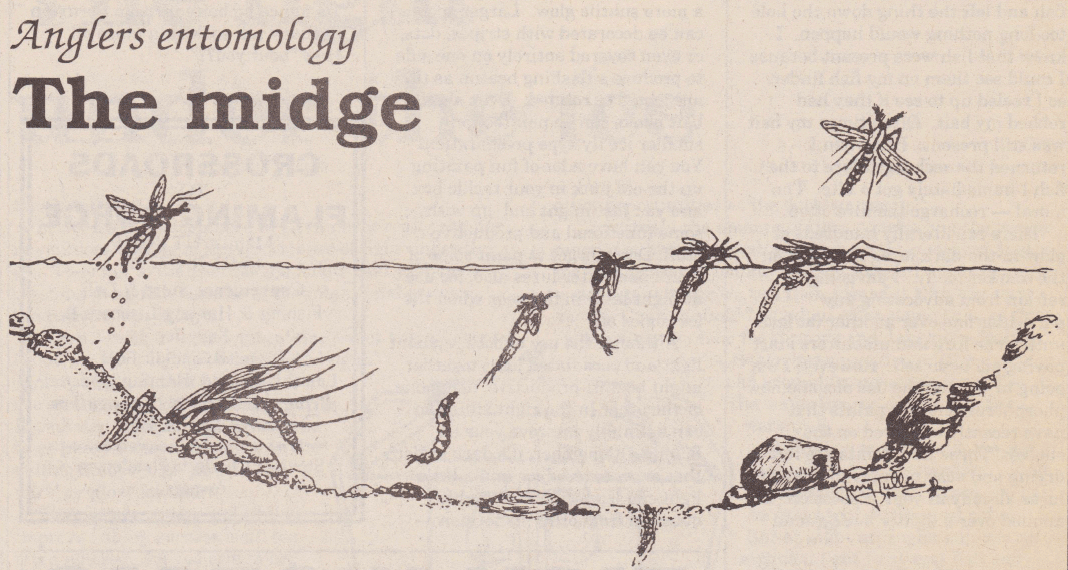

The female midge lays eggs on or below the water surface. Once in the water the eggs drift to the bottom and in a few days or weeks, hatch into larva. The larva drift in the current or live on various types of bottom materials. When the larva matures it goes through a metamorphosis and turns into a pupae. After a few days to a week the pupae leave the safety of the bottom and swim with a slow wiggling motion to the surface. Once at the surface they float there, suspended vertically until they emerge as adult midges. The midge must float on the surface while it dries its wings and becomes ready for flight.

Within a few hours or days after emerging, large egg-laying midge swarms form over the water and the cycle starts over

again.

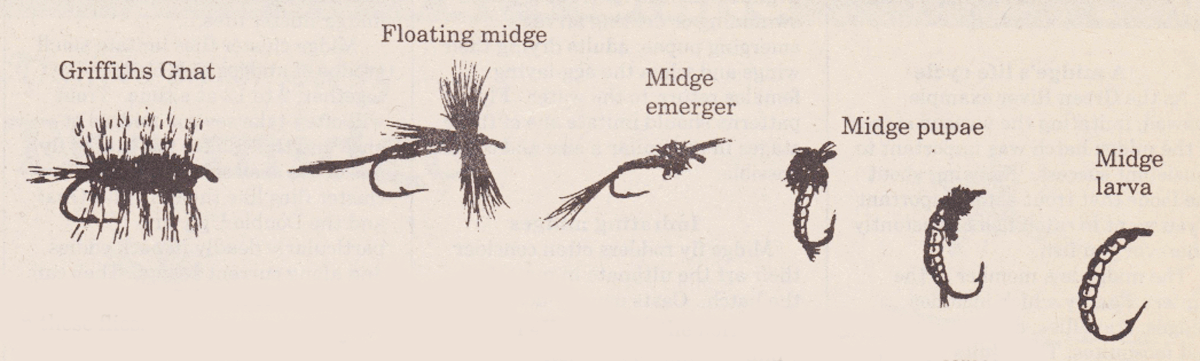

The four times when midges are available as food for trout are as swimming or drifting larvae, emerging pupae, adults drying their wings and when the egg-laying females return to the water. Fly patterns should imitate one of these stages in as similar a size and color possible.

Imitating midges

Midge fly rodders often consider their art the ultimate in matching the hatch. Casts usually don’t need to be very long but the leaders should be long and light so the presentation is delicate and natural looking. The naturals are often very small and most midge patterns are also very small. The exception is midge cluster flies.

Midge cluster flies imitate small groups of midges that bunch together, 2 to 12 at a time. Trout will often take several midges at once and this makes the cluster fly one of the easiest to imitate. Midge cluster flies like the Griffith’s Gnat

and the Double Ugly are particularly deadly in back eddies and along current seams. They can be anywhere from size #20 to #12. Because they are generally bigger than most midges, they are much easier to see and fish properly. Just about anyone that can get a drag-free drift over a fish can catch fish on these flies.

When fish are extra selective, I like to tie a piece of light leader material to the cluster fly hook and attach a small, fairly exact midge pupa imitation. Fish are often more receptive to a natural looking bug hanging in the surface film than a larger cluster fly. The bigger fly becomes a strike indicator. At other times the fact that a cluster fly does look different actually helps the fish key in on it amidst hundreds of naturals. A perfect imitation may get lost in the hoards.

When fish are feeding on midges but there are not very many on the surface, the natural midge is best. Carry several black, brown and cream midges in #24 to #16 sizes.

Nymphing with midges is a delicate process. Forget using a bright, gaudy strike indicator. Use instead, a dry fly or CDC (Cul De Canard) feather as a strike indicator. Occasionally, when the light is right, you can simply grease the leader to within a foot or two of the fly with fly floatant and watch the leader for a hesitation.

The hook should be set quickly but gently. The small, sharp hooks don’t need much.

Tackle for midges

I’ve occasionally fished midges with an 8 weight but a 3 to 5 weight rod is preferable. The lighter rods can deliver the fly more delicately and accurately. Light lines also get better drifts on the water, helping the midge look natural.

Leaders are partly a personal thing. When fish are selective and leader shy you might need a 12 to 15 foot leader that has a long, limp tippet. Usually a 9 to 12 foot leader is plenty if you can get a good drift.

Tippets of 4X to 7X are the norm. If you get rejects, try a smaller fly and a lighter tippet.

Another trick for leader-shy fish is to position yourself upstream from the feeding fish and fish downstream. Cast downstream and draw the rod back before the line touches the water. Drop the fly several feet above the fish and allow enough slack line to let the fly drift past the fish. This gives the fly to the fish fly first and they are not as likely to reject the offering because of the leader. Downstream hook sets must be delayed for best hookups.

Where and when

Midges hatch many days of the year but are the most abundant food for the trout in the cooler months when other hatches are few or nonexistent. Mid-winter is a fun time to fish midges because it can be below freezing but the fish will still be rising or feeding on the larvae. You may not actually see midges on the water but if the fish are dimpling the water with a delicate rise, chances are good that there are a few midges around. Sometimes the rises are so gentle that you may think your eyes are fooling you. The fly sometimes just disappears. Rise forms that are splashy, make large rings or leave a bubble are probably not fish feeding on midges. Look for “midging” fish in back eddies, on current edges and on the tail-out or slick of a pool. In riffles, the choppiness of the water makes dry midge imitations difficult to track but larvae imitations below a small strike indicator are sometimes deadly.

Lake midges should not be overlooked either. Almost as soon as the ice comes off the lakes, midges start hatching and fish will be following these insect movements with lots of interest. Spring often brings huge midge hatches that make the shoreline vegetation buzz with life.

Lake midge patterns are often slightly bigger than their stream cousins (size #16 to #10). Here too, the angler should use delicacy in presentation. A 12 to 15 foot, 4X or 5X leader on a floating line does the job in clear water. Other times you need to go deeper with a #2 sink rate fly line. Fish the edges of weed beds and channels in the weeds. The downwind end of a bay or a point often concentrates a scum-line of midges where fish will be found feeding.

Try midges and you too may be hooked on this delicate, intriguing, sometimes frustrating but always rewarding method of fly fishing. It will help you catch fish more often and it’s plain fun. These prolific little critters are very important to the trout and so they should be to the well rounded angler as well.

Grab a few midge patterns and head for the stream or lake.