By Dan Webb

By Dan Webb

A four-hour car trip from Salt Lake City brought us to Nevada’s Snake Mountain Range. We went into the Great Basin National Park visitor center and waited for the tour. Our guide was a ranger named Abby.

Looking at the mountain we were about to enter, I would never have guessed there were miles of caves inside. We entered a man-made passageway into the Lehman Caves, because the natural entrance requires a rappel down through a small tunnel. Our tunnel was about 50 feet long, with a huge, locked wooden door at its end.

Being in such a damp, sterile place made the next site we experienced quite a shock. Our tour-guide informed us that, way back when the caves weren’t an attraction, Indians tribes used the cave as a burial site. She asked us to not talk all the way through the tunnel to show respect and reverence.

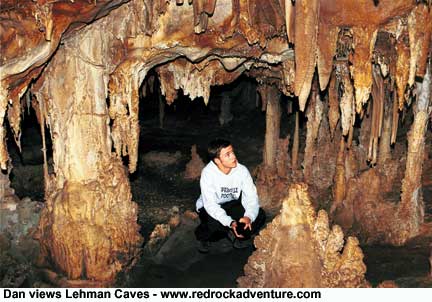

When the large wooden door opened, we walked into the first part of the cave, and were met by a breathtaking view. The first room was a large cavern called the Gothic Palace, for obvious reasons. The cave decorations, very dark and mysterious, were highlighted by a white light fixture placed inside. The huge stalactites loomed above, and the towering stalagmites stood tall beside us.

The sheer weight of the room hung down on you as you realized there was an entire mountain over you, pressing down on walls and ceiling.

The tour then took us through a tunnel full of magnificent rock structures, into another cavern called the Inscription Room. This room had a domed ceiling with little broken-off stalactites. There was hardly a rock creation in the first part of the room; the decorations mainly chose to stick on the sides of the chamber. The room’s name was properly given; as you looked up at the ceiling, you saw the entire thing was covered with initials and dates. They were hard to make out because of the lighting and because they were so close to each other, you could hardly decipher which last name initial went with which first name.

Abby told us the more recent signatures were made with charcoal but the older ones were burnt into the stone itself. Then she pointed out some of the oldest dates, reaching far back into the late 1800s. We were told that they signed their names to prove they’d made it as far as Lehman would allow people to venture.

The tour then took us through many other caverns containing some of the most irregular looking rock formations I have ever seen. One kind really caught my attention: helictites, which grow in the most alien way you can imagine. The incredibly slow water movement through the helictites causes them to form in a chaotic, sprawling manner, some growing straight up, some straight out, while others grow twisting around each other.

There were also flowstone towers that appeared to be made from molten rock, standing majestically tall and mighty. They were very large and thick at the bottom, tapering as they went up.

But the most curious formations I found were the shields. Lehman Caves is most famous for its many shields. Shields look like some sort of clam flattened on the top. The shield is made of two plates separated by a thin space where water comes out. The shields form from a crack in the wall with water that has calcium carbonate flowing through it. As the water comes out of the crack, it releases dissolved carbon dioxide. The water, unable to hold the calcium carbonate, deposits the mineral on the crack.

The best-known shield is a very large one called the Parachute. It sits in the Grand Palace, one of the last rooms you visit. The Parachute hangs some 20 feet off the ground, and is adorned with long skinny, wavy stalactites that come together at the tip.

At the end of the tour, we double-backed and headed down another tunnel, out of the cave.

Facts about Lehman Caves

1. These cave is unique because it is profusely decorated with a great variety of calcite formations. It is one of the most beautiful caves in the U.S.

2. The name is plural, but it is just one cave with many rooms and passages. It is located in Great Basin National Park, on the Utah/Nevada border west of Delta.

3. It was discovered in 1885 by rancher Absalom Lehman. Soon thereafter he began charging to guide guests through its dark chambers.

4. Native Americans knew of the cave and used the entrance as a burial site. Evidence suggests they never explored its far reaches; the natural opening had to be enlarged to allow Lehman and his friends to enter conveniently. Cave structures were broken off in several areas to allow explorers to penetrate some passages.

5. The cave consists of a series of passageways and chambers extending almost horizontally into the mountain. It is not a particularly large cave. Major passages extend about 1/2 mile into the mountain. There are many side passages, some too narrow to explore. It isn’t known how far they go back.

6. The cave was named a national monument in 1922, and became part of Great Basin National Park in 1986. Wheeler Peak is the other main attraction in the park. The peak is a great place to camp and hike, and offers a limited amount of fishing in small streams and lakes.

7. The cave began forming about 70 million years ago when carbonic acid (formed from water and carbon dioxide gas) began to leach through cracks in the limestone and started carving and decorating the cave. It is a "living" cave–meaning the formations are still growing. Major types of features are listed below:

a) Soda straws–tiny and hollow in the middle so water can percolate to their ends.

b) Stalactites–hanging down from the ceiling.

c) Stalagmites–growing up from the floor.

d) Columns–formed when stalactites and stalagmites join.

e) Popcorn–irregularly-shaped calcite balls growing on the cave walls.

f) Shields–rare in other caves but common here. They are disk-shaped structures, often with other decorations attached. Lehman has the largest known concentration of shields.

g) Draperies–hang down from the ceiling in many places. Cave "bacon" is common.

8. Rangers guide people through the cave. Tours of various lengths are offered. The shortest just goes into the first room. Other require a 60-minute or a 90-minute walk.

9. Visitors aren’t allowed into all of the rooms. The "Talus Room" is closed to public access. It is deemed unsafe because rocks there are moving.

There are many other caves in the national park and the surrounding area. People are encouraged not to explore caves on their own. If you want to get into caving, join a club. There are caving clubs in most major cities. The National Speleological Society web site, www.caves.org, lists local chapters.

Copyright Dave Webb