By Golden Webb

By Golden Webb

I’ve wanted to drive the Flint Trail ever since I read about it in Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang. In the book, George Washington Hayduke and Seldom Seen Smith use the road to escape Bishop J. Dudley Love and his posse after performing a little eco-sabotage down in the vicinity of a certain loved-by-some, hated-by-others reservoir (Lake Powell). Their choice of the Flint Trail as the avenue of their escape was a simple and practical one. Not only is the road rocky, sandy, rutty, washed-out, and virtually impassable, but it leads into a maze. Literally. The Maze, the Maze District of Canyonlands National Park.

Trekkies of the world forgive me if I get the following wrong somehow, but if I remember right in The Wrath of Khan Captain James T. Kirk takes the disabled Enterprise into some kind of Nebula-like electric cloud-thing to elude the pursuing Khan, a kind of maze of vaporish electricity and energy. The jumbled and chaotic canyon lands surrounding the Orange Cliffs, under which the Flint Trail runs, is southern Utah’s version of that Star Trek Nebula cloud. Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch used the Dirty Devil River drainage on the western side of the Orange Cliffs as their hideout, so much so that the area became known as Robbers’ Roost Country. This is truly the kind of country one could lose oneself in – disappear into.

Now, since most people don’t want to disappear and don’t want to become lost, as a general rule they have stayed away from this forbidding landscape, ensuring that it has remained the kind of pristine, primeval wilderness that is increasingly hard to find in today’s modern world. That there is a road at all in this crazy jumble of canyons, mesas, and pinnacles is incredible. What’s even more incredible is that people actually call the Flint Trail a road. My Suzuki Sidekick certainly isn’t convinced. By the end of my Flint Trail adventure she was bruised, scraped, smoking with red dust, and had a concussion worse than all three of Steve Young’s combined. If questioned under oath, she (the vehicle) would testify that the Flint Trail is in point of fact not a road at all but rather a strung together series of sandstone ledges, dry washes, boulder fields and acrophobia-inducing contour lines up and down the sheer faces of cliffs.

Now, since most people don’t want to disappear and don’t want to become lost, as a general rule they have stayed away from this forbidding landscape, ensuring that it has remained the kind of pristine, primeval wilderness that is increasingly hard to find in today’s modern world. That there is a road at all in this crazy jumble of canyons, mesas, and pinnacles is incredible. What’s even more incredible is that people actually call the Flint Trail a road. My Suzuki Sidekick certainly isn’t convinced. By the end of my Flint Trail adventure she was bruised, scraped, smoking with red dust, and had a concussion worse than all three of Steve Young’s combined. If questioned under oath, she (the vehicle) would testify that the Flint Trail is in point of fact not a road at all but rather a strung together series of sandstone ledges, dry washes, boulder fields and acrophobia-inducing contour lines up and down the sheer faces of cliffs.

Roughest Road in Utah

And she’d be telling the truth. The Flint Trail is the roughest routinely traveled road in Utah. I say routinely traveled in the sense that tour guide operators, rangers and hard-core 4WD enthusiasts drive it often enough that the hedgewall-like line of weeds growing on the drift sand ridge between the tire ruts hasn’t grown more than three feet high and the tips of the fang-like boulders jutting upward toward the intimate parts of your vehicle have been sanded down and are burnished black from countless violent encounters with innocent undercarriages.It took me over eight hours driving time to travel the 100-mile length of the trail from SR24 to Hite Marina on Highway 95. That’s driving time. I’m not including my detours to Horseshoe Canyon, the Maze Overlook, and a couple pit stops. Your vehicle is gonna stay in the 1st and 2nd gears of 4WD and 4WD-Low for most of the 60 miles from Highway 95 to Hans Flat. If you try and go any faster your vehicle will not make it out alive.

The Flint Trail begins on Highway 95 between the Dirty Devil and Colorado River bridges. Traveling northeast, it makes a couple of huge detours around the branches of Rock Canyon, turns a corner around the jutting prow of a mesa and then heads northeast over the Andy Miller Flats. Looking to the east, one can see the chasm of the Colorado and just beyond that the yawning mouth of Dark Canyon. To the west soars the towering wall of the Orange Cliffs. The road continues northeast between the Orange Cliffs and the Colorado’s Cataract Canyon onto Waterhole Flat, passing along the way The Cove and the Black Ledge to the west and Red Point to the east. Thirty-two miles from Highway 95 you arrive at a signed junction. The track to the west leads over Sunset Pass and into North and South Hatch Canyons of Dirty Devil River country.

The track to the east wraps around Teapot Rock, Red Cove, and then tumbles into Ernies Country and the Land of Standing Rocks. This area makes up the southern portion of the Maze District and is the most remote, least visited region of Canyonlands National Park. The place is full of wonders. The Fins, The Wall, the Doll House, and The Plug; Lizard, Standing, and Chimney rocks; Whitmore, Tibbet, Muffin, Cave and Beehive Arches. Ever heard of them? Nope. But these natural wonders are as spectacular and beautiful as anything on earth. This track to the east is definitely worth traveling, a worthy detour from the Flint Trail into a magical landscape.

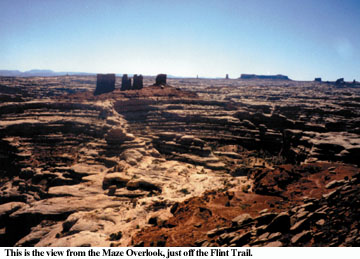

The Flint Trail is the middle road and it continues north-northeast toward the southeast corner of the Orange Cliffs – an area called Lands End. This is where the fun begins. The road contours up onto the cliff and takes an extremely rough, rocky, torturous tack up along the finger-like peninsula of Lands End until it arrives at the second signed junction. The road heading northeast leads 20 miles through the Elaterite Basin to the Maze Overlook. This is the jumping off point for those adventurous enough to brave The Maze.

The Maze is a Medusa’s head tangle of many-fingered canyons that seem to be trying to bleed into each other but are kept apart, barely, by sinuous, knobbed walls of stone. Think of five nests of snakes suddenly released at the same time and you begin to visualize the writhing convolutions of Jasper, Shot, Water, South Fork and Horse Canyons. This is a place that would make Daedalus shake his head with envy, make King Minos fire Daedalus in favor of the creative genius behind its design, and make Theseus shake in his sandals and drop his spool of string. Heck, without topo maps even the Minotaur would get lost in there. The Maze District of Canyonlands National Park makes the Labyrinth of Crete look like an empty Walmart parking lot.

So by all means drop off the rim of the Overlook and get into it. Make your way into South Fork Canyon under the Chocolate Drops and follow the labyrinthine passageways of stone to Pictograph Fork and its Harvest Scene, a spectacular panel of Barrier Canyon-style rock art that depicts . . . well, no one is really sure what it depicts. Barrier Canyon-style rock art is the oldest pictography on the Colorado Plateau and is equated with the Archaic Culture. These mysterious peoples antedate even the Anasazi. The Harvest Scene, located in a portion of Pictograph Fork called the Bird Site, is 2,000 to 4,000 years old and consists of a series of ghostly figures with tapering anthropomorphic forms that are forbidding and almost demonic in aspect. They seem to stare back at you out of the rock, whispering some strange ancient message that will perhaps remain forever unknowable. On the spooky and cool scale of 1 to 10, the Harvest Scene rates a 12.

From its junction with the Maze Overlook road the Flint Trail heads southwest into Flint Cove and then in a series of tight switchbacks climbs straight up a sheer wall to the top of the Orange Cliffs at Flint Flat. These switchbacks are extremely steep, tight, and rough. They literally switch-back, with no curving transition between the east sloping and west sloping sections of road. At each corner you have to do a three to four point turn before you’re finally pointed in the right direction. These maneuvers must be performed on a steep slope with a sheer cliff to one side and no room for error.While I was climbing these gruesome switchbacks it finally occurred to me what a "hairpin" curve really is. Think of the U-shaped angle formed by an unclasped hairpin or barrette. Now clasp the barrette. The corners of those switchbacks on the Flint Trail are tighter than a clasped barrette, more like a sharp V than a U.

I’m belaboring this point because this section of road is nothing to be trifled with. If two vehicles happen to cross paths there, one going up and the other coming down, well, bon chance. There is no room to maneuver, no space to pass, and you sure as heck wouldn’t be able to backtrack in reverse. Drive this section of the Flint Trail with extreme caution.

Once up top the road heads west to the third signed junction. The track south passes Lands End and traverses the span of the Big Ridge, a colossal land bridge that separates the Maze District and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area from Happy Canyon and the Dirty Devil River complex. The road terminates at The Pinnacles and provides ambulatory access to the South Fork of Happy Canyon.

The Flint Trail continues north from the Big Ridge junction through the pinyon/juniper forests of the Gordon Flats. Just before French Spring is a fourth signed junction. The North Point Road branches off to the northeast, an extremely rough 4WD track that traverses the top of North Point, a branching limb of the Orange Cliffs that separates Millard Canyon from Horse Canyon and The Maze. The route leads 8 miles to two spectacular campsites, one at Panorama Point and the other a few miles farther on called Cleopatra’s Chair.

Panorama Point is a place that is beyond beautiful. Its dizzy aeries provide unrivaled views into and over The Maze and beyond to the distant Needles. In 1993 I celebrated graduating from high school by heading south and ended up kind of arbitrarily at Panorama Point, arriving after nightfall and without an appropriate appreciation for the amazing nature of the place. The next morning I watched in awe as the first pink rays of the rising sun bled through the peaks of the La Sals and flooded into the Needles and The Maze with a pure and piercing light until it seemed that the stone itself was not just reflecting the luminous morning hues but giving off a shimmering, lambent glow from within. The land, and by extension the sky, the light, the air, the universe – all seemed alive, sentient, aware, even benevolent, not only conscious of my presence but appreciative and embracing of it, as if my human sensory, emotional, and spiritual experience of that magical sunrise was making it real, a tangible, measurable, validating and meaningful event. It’s hard to be an agnostic or an atheist when confronted with the mystical beauty of Panorama Point.

From the North Point junction the Flint Trail goes northwest past French Springs and beautiful Millard Canyon to the Hans Flats Ranger Station. From the ranger station a 4WD track branches off to the north onto The Spur where it follows the rim of the northern Orange Cliffs for many miles until a side spur branches off to the east and ends at the rim of Horseshoe Canyon near The Great Gallery.

Horseshoe Canyon was formerly called Barrier Canyon and rock art images in the Great Gallery establish the Barrier Canyon-style. The gallery is considered by many to be the premier ancient rock art in North America. The supernatural power of these images is undeniable, large front-facing human-like figures colored blood red by the mineral hematite. The Great Gallery is so perfectly preserved, so aesthetically pleasing, so perfectly refined in its compositional technique and graphic creation, and its figures so haunting and mysterious, that it not only sets the standard by which all other rock art in North America is judged, but is ranked along with the works of the Monets and the Picassos as being among the world’s finest art masterpieces.

From Hans Flat the now graded and well maintained dirt road heads west onto Robbers’ Roost Flat and then curves north toward the fifth and final signed junction. The road heading northwest leads to the western and most popular access to Horseshoe Canyon, a moderately steep former 4WD track that drops down from a sandy parking area and enters the canyon a few hundred yards upstream from the so-called High Gallery and 2.5 to 3 miles from the Great Gallery. This is a truly lovely canyon. Even without the spectacular rock art, Horseshoe Canyon would be worth visiting if only for its remoteness and its wild and lonely peace and stillness.

The main road heads west from the Horseshoe Canyon junction and passes into the low flatlands and occasional undulating sand dunes of the San Rafael Desert. Soon the corrugated spine of the San Rafael Reef looms up on the western horizon, and after a few more twists and turns you arrive trailing a 50 yard comet-tail of dust at a strange thing, a black, utterly smooth and mathematically perfect linear stretch of State Road 24, the highway that connects Hanksville to 1-70. Your Flint Trail adventure has come to an end.

As you spin off onto SR24 and accelerate, shifting up through the gears from 3rd to 4th for the first time in 100 miles, then slip into 5th and give your vehicle its head, I’m sure you’ll be tempted as I was to unroll your windows in the hope that the resulting maelstrom-like swirling vacuum of air will suck out the accumulated drifts of red dust coating every exposed surface. A few billowing clouds may rise from your dashboard and flow into the slipstream, but most of it will remain stubbornly in place, stickily adhering to the floor, the ceiling, the seats, the stereo system, the plug-in portable CD player, your eyelids, your arm hairs, the cilia on your cheeks, and the stubble on your chin and jaw line. But a dusty car is a small price to pay for the memories of the Flint Trail that, like the dust, will adhere to the contours of your paradigm of life and constantly serve as a reminder that the world is a wild and mysterious place, full of beauty and wonder.

Getting there/rules and regulations

The Flint Trail can be accessed from the south where it joins Highway 95 between the Colorado and the Dirty Devil Rivers. The Flint Trail is not signed as such at the turnoff but there is an incongruous looking stop sign at the junction, and a few hundred yards down the dirt road are a couple of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area placards and an interpretive kiosk.

The Trail can also be accessed from SR24, the highway that connects Hanksville to 1-70. Near the signed Goblin Valley junction to the west you’ll see a graded dirt road branching off to the east. A sign, placed a little back from the highway, gives the mileages to Horseshoe Canyon, The Flint Trail, and even Hite. This is your road.

It is very important to go prepared. Make sure before you start out that you have a tank of gas that is full to the brim. It’s always a good idea to bring along some extra gasoline. Store it in an approved container on the outside of your vehicle, never inside. An emergency kit for unanticipated contingencies should include a shovel, a tire pump, a spare tire (or two), extra water and food, tool kit, a battery jumper cables, a towrope or chain, extra oil, and anything else you can imagine needing desperately in a breakdown situation a hundred miles from any garage. Go prepared for the worst.

Backcountry permits are required for overnight stays in the Canyonlands backcountry. They are good for a maximum of 14 days. Backpackers can stay up to seven consecutive nights in any site or zone. Vehicle campers can stay at a camping area three consecutive nights before having to relocate. Primitive campgrounds are located in Horseshoe Canyon, at Panorama Point and Cleopatra’s Chair on North Point, at the Maze Overlook, and in the Land of Standing Rocks at The Wall, Standing Rock, Indian Cave, Chimney Rock, and the Dollhouse.

The Backcountry permit fee for overnight backpacking in the Maze District is $10 with a group size limit per permit of 5 people. The Backcountry vehicle permit fee for the Maze is $25 with a group size limit per permit of 9 people/three vehicles. Permits may be reserved in advance by calling (435) 259-4351 or by fax at 259-4285. More information on rules and permits can be had at the Hans Flat Ranger Station.

(Published Nov., 99, in Utah Outdoors magazine)