Story and photo by Tom Till

Story and photo by Tom Till

Master landscape photographer

Utah Outdoors, July 2002

IF I HADN'T CHOSEN photography as a career, my dream job would be a weatherman. I’m fascinated by the changing seasons and changing skies, and they play a huge role in my photographs.

Clouds have an integral role in all outdoor photography as light sources, light controllers, and as subjects. Many compositions I plan require clouds to flesh out a scene. I won’t photograph a huge natural arch, for example, until I have clouds to fill the expanse inside the opening. For me, there has to be something you see through the arch, and clouds fill the bill. I'm finicky about the clouds I like to use Buttermilk clouds, rate, symmetrical and repetitive mid-level beauties are my favorite, although I also move the more common fair weather cumulus and tropical cumulus varieties. When cumulus clouds darken to blue or black, but sunlight still shines through, I can use one of my favorite effects - chiaroscuro, a lighting effect prized by painters as the powerful juxtaposition of light and dark and as the tension that comes from those polar opposites.

Sunset clouds are diligently sought by photographers and graduated neutral density filters, or GND, help us work the bright sunsets into nature photos that include a darker, unlit foreground. A new GND filter offered by Singh-Ray Company is particularly adept at pulling off this balancing act. Called the Daryl Benson GND, after the photographer who first suggested it, the filter starts out darkest in the middle, an then gradually diminishes to neutral density towards the top, the opposite effect of most GNDs. My initial tests with it shooting a brilliant sunset with an unlit ancestral Puebloan ruin in the foreground, have proven very successful. The ruin is easy to see and naturally exposed, as is the bright sunset.

Sunset clouds are diligently sought by photographers and graduated neutral density filters, or GND, help us work the bright sunsets into nature photos that include a darker, unlit foreground. A new GND filter offered by Singh-Ray Company is particularly adept at pulling off this balancing act. Called the Daryl Benson GND, after the photographer who first suggested it, the filter starts out darkest in the middle, an then gradually diminishes to neutral density towards the top, the opposite effect of most GNDs. My initial tests with it shooting a brilliant sunset with an unlit ancestral Puebloan ruin in the foreground, have proven very successful. The ruin is easy to see and naturally exposed, as is the bright sunset.

One of my favorite atmospheric conditions — and one that causes the most skepticism in people who frequent my gallery in Moab - is what l call an anti-sunset. Much rarer than the normal brilliant cloud sunsets which occur in the west, anti-sunsets occur when clouds opposite the sun in the east light up with the fire, color, and brilliance of their counterparts. With these sunsets, the landscape below is still lit by sunlight or residual sunlight, and again by using a GND filter, the bright sky can be tamed to match the darker foreground.

Since most people expect to see landscape features as silhouettes in a normal sunset, the anti-sunset allows the viewer to see a normally lit foreground with a dazzling sunset above. Since this phenomenon is unfamiliar to most people, images that play up the anti-sunset can look too good to be true, although they exactly portray what the eye sees.

A photograph I made in the Pinnacles Desert in Australia at Namhung National Park, north of Sydney, is one of my most successful anti-sunset prints. After a week of shooting and scouting the area, I knew that the highest pinnacles, giant above ground stalagmites, would get the last best sun of the day. I also noted that this stretch of coast along the Indian Ocean provided Technicolor sunsets every night.

On my last night, I was awarded a fiery anti-sunset while residual light still illuminated the highest pinnacles. Using a .9 soft Lee GND filter to block the sky, I made a series of images fighting a 20-mph wind. Fortunately, one shot was sharp enough to become an extremely popular 30x40 print in my gallery, and a blockbuster image for stock sales. We have a number of gallery visitors who swear the image must be some kind of computer manipulation instead of the raw, handmade print that it really is. I was extremely happy with myself as I drove the gauntlet of nighttime kangaroos, Wallabies, and emus back to camp.

Clouds are also the nature photographer’s premier tool to control lighting. The white light from overcast clouds is perfect for shooting moving water, forest interiors, close-ups, or any subject where reduction of contrast by flat, cloudy lighting is required. In the Southwest, cloudshine can sometimes work back wards when the underbellies of white clouds take on the red color of the landscape below. This beautiful phenomenon occurs most often in Monument Valley when colossal cotton candy clouds tower above and reflect the magenta sands and cliffs below.

My favorite lighting for canyon country and other landscapes is a mix of sun and cloud with spotlighting, where pieces and pans of the landscape are lit by constantly changing and moving sunlit areas. Spotlighting is great for giving a three-dimensional feel to a nature photo, and for softening the sharp, harsh shadows that occur in mountainous terrain.

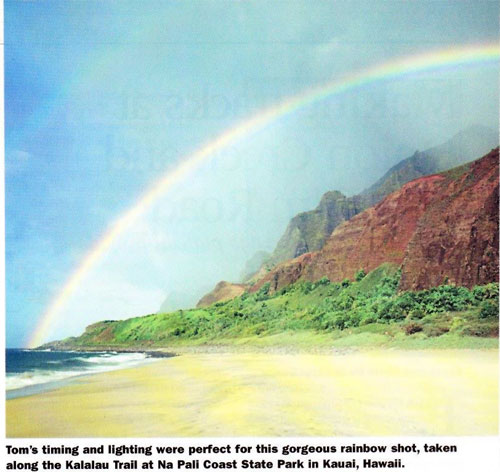

When clouds thicken and rain may become a possibility, my storm tracking senses become sensitized and I run off to chase rainbows. Rainbows have always been a prized subject for me; it’s as if the more elusive and ephemeral the prey, the more excited and focused I become, and I’ve gotten very good at chasing them down. As with sunsets, I feel a rainbow or a good sunset by itself is not enough there must be a beautiful landscape or other subject to complement the sky pyrotechnics.

To find rainbows, which only occur for a short period after sunrise and before sunset, I look for dark black rain-laden clouds or watch for sheets of falling rain, all of which must be opposite the sun. If the clouds are moving fast and are thick around the sun, rainbows may be too short-lived to capture on film.

I’ve photographed rainbows all over the world, and the best conditions occur in showery, come-and-go rainstorms most Common in the tropics. Ireland, which essentially has tropical weather pattern because of the Gulf Stream, is a champion rainbow locale, as are the Hawaiian Islands. On Kauai for example, a rainbow forms nearly every evening on Kalalau Beach when the sun drops past the desert side of the island and shines toward the easterly rain forest side.

Desert Southwest monsoons and showers are also great for rainbows. On a Grand Canyon River trip I waited in a small cave until the deluge ended and was rewarded with a spectacular double rainbow seeming to come directly out of the Colorado River. Luck, yes, but as Woody Allen says, 80 percent of success is showing up, and many photographers don’t show up when the weather turns foul.

A final hint: I almost always use a polarizing filter to intensify the colors of a rainbow, though I take care in brushing water off the filter as it may move and make your rainbow completely disappear.

In upcoming articles I'll continue my series on weather and the sky, with discussions on fog, snow, the moon, star trails and unusual phenomena like ”glories,” and the total solar eclipse.