Story and photo by Tom Till

Story and photo by Tom Till

Master landscape photographer

Utah Ourdoors - June 2002

WITH THIS ISSUE, I’m beginning a multi-part column on weather and its crucial role in great landscape and nature photographs. Many beginning photographers assume that stormy weather is a signal from the cosmos to put their camera away, but I hope to dispel that notion and sing the praises of snow, fog, rain, lightning and the other spectacular surprises that unusual meteorological conditions can provide.

As Paul Simon sang in his green song ”Kodachrome,” trying to make all the world a sunny day is still the standard for many of the clients who purchase my work for publication. Travel publications especially want to see and publish mostly imagery of pleasant sunny days without the threat of a dark cloud, and I shoot my fair share of photographs in that vein. Living in the desert southwest with its seemingly endless blue-sky days provides me with plenty of opportunities to use pure, unadulterated sunlight as my light source.

But when the stormy days come, especially in the monsoon season of July to September, or when winter storms arrive, I feel a heightened sense of anticipation knowing that the possibilities for unusual lighting have greatly increased, and my photographic work takes on a new sense of urgency.

But when the stormy days come, especially in the monsoon season of July to September, or when winter storms arrive, I feel a heightened sense of anticipation knowing that the possibilities for unusual lighting have greatly increased, and my photographic work takes on a new sense of urgency.

Any study of the work of Ansel Adams shows what a large role weather and sky phenomena play in his seminal work. Many of my favorite Adams images of Yosemite Valley include fog and snow, transforming an already stunning landscape into even further realms of moodiness and mystery.

Although Arizona Highways is a state-owned publication with the sole purpose of bringing tourists to our neighboring state, 1 credit the magazine with the courage and innovation to publish, beginning in the 1950s, landscape and nature photographs that depict the state's infinite natural wonders, in full double-page glossy glory, in all kinds of bad weather.

My father, a farmer, always had his eye to the sky, and I’ve inherited his interest in weather and have spent a great deal of time studying meteorology and trying to use what I've learned to produce interesting photographs. My ultimate dream is to get a good shot of a tornado (I saw several as a child), and I hope someday to join a tornado chasing team in the Midwest to bag the ultimate weather prize. I also plan to shoot my second total eclipse this year in Australia, in December. Although totality will last only 30 seconds, the eclipse will be unusual in its closeness to the horizon, hopefully providing me the opportunity to use some element of the outback landscape in the shot.

Let’s dive into weather with one of the most exciting, dangerous and beautiful weather conditions of all - lightning. Because lightning on a regular basis kills Utahns, photographers must approach the unpredictable and deadly subject with utmost caution. Although I don't know of any photographers who have been killed while photographing lightning, I've read about a Florida photographer specializing in lightning who has had numerous cameras and tripods transformed to heaps of smoldering molten goo, underlying the fact that metal equipment can become extremely efficient lightning rods.

To photograph lightning safely I use the following strategies: I often set up the camera on a tripod, open the shutter on bulb setting with a wide open aperture, then retire to the safety of a car. Standing next to a tripod during a lightning storm is suicide, in my opinion, especially if the strikes are frequent, powerful and close.

If the lightning is far enough away so that no thunder is heard, you are most certainly safe, but I have had bad luck making distant lightning show up on film. Unfortunately, lightning looks better and registers mote strongly on film if it is closer and more dangerous -- a catch-22 situation.

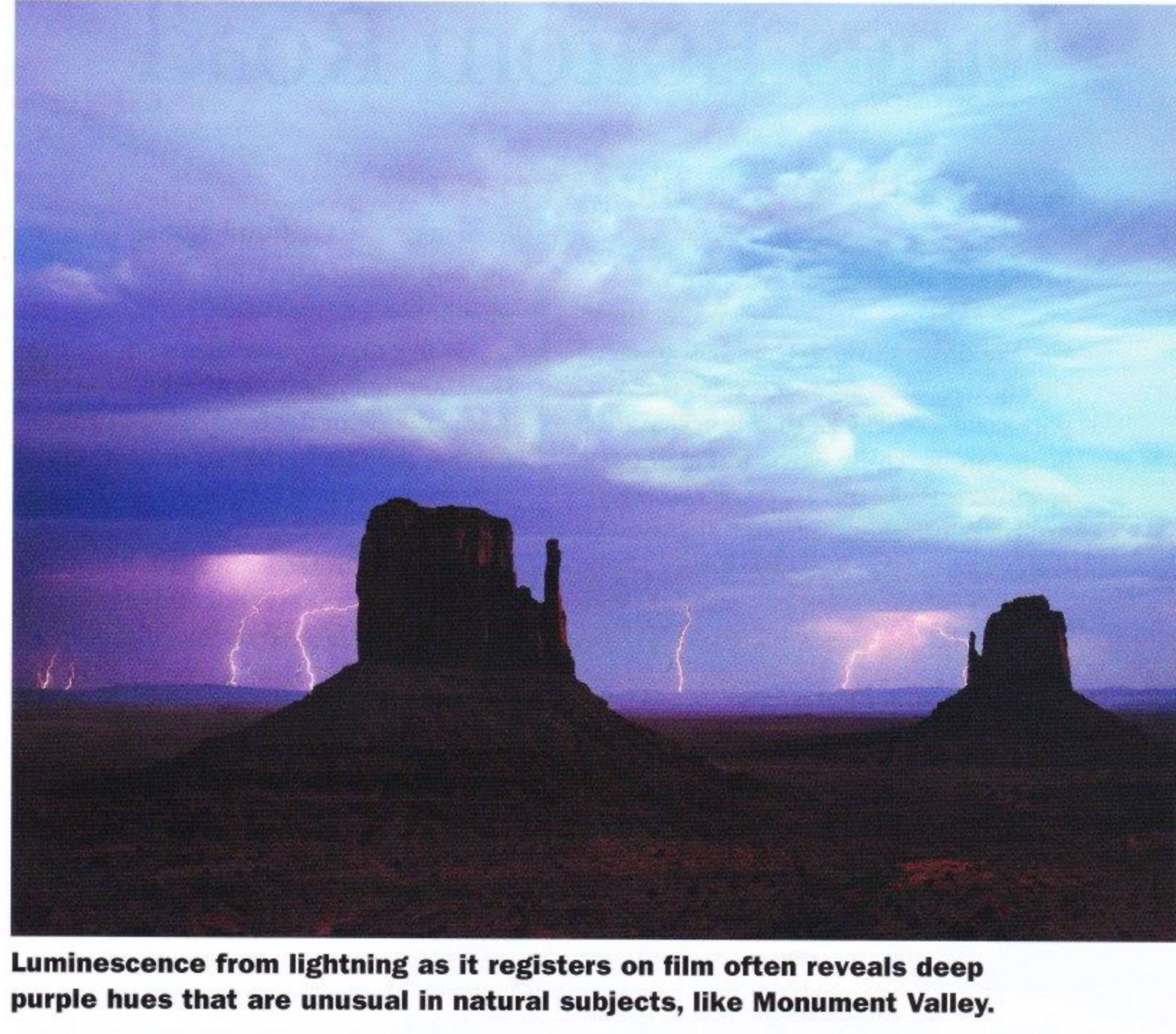

Two of my most successful lightning images involved moonlight to illuminate the landscape being attacked by thunder storms, adding light on the forms of Monument Valley and Balanced Rock in Arches National Park, to show the lightning as part at the overall scene. Having this moonlight was pure luck, since the thunderstorm had not progressed far enough east to cover the rising moon. Both shots were taken with a Pentax 6x7, a normal lens (90 mm) and Fuji 100 film shot at 2.8 aperture on bulb for 5 minutes. A lot of lightning photography is pure luck, so multiple exposures may he required to get one keeper. Without the moon to illuminate your lightning-attacked landscape, multiple strikes can sometimes provide enough light (especially if dangerously close) to light up the landscape.

I love the colors that lightning registers on film, often deep purple hues that are unusual in natural subjects, and sometimes reds, blues and even greens. An interesting twist to lightning photography was done by Marc Muench recently, where he used strong color filters (changed after each strike) to produce a photograph of multi-colored lightning forks.

A participant in one of my recent photo workshops had excellent lurk shooting lightning under the guidelines I’ve presented here, and safety was not a concern since he was along the bottom of the Colorado River while the lightning danced thousands of feet above on the temples of the Grand Canyon. Unfortunately his efforts were ended by a deluge of rain, another of the problems or lightning photography.

To recap:

1. With lightning photography, safety is paramount. Stay in your car if lightning is close, or your position is higher than the surrounding terrain. Avoid shooting from mountaintops or high ground, and leave the are immediately if you hear thunder or experience pre-lightning phenomena (tingling sensations, hair standing straight up or other intense static electricity discharges). If caught in the open during a storm, place your metal camera gear some distance away from you and seek shelter.

2. Understand that even if you are safe in your vehicle, your camera and tripod can he at risk from a strike.

3. Use fast film (100-400 ISO) and open your shutter with the bulb setting. I have best luck with 2-5 minute exposures to capture several strikes, although I did get a lucky lightning shot during the daytime with a polarizing filter and an exposure of 4 seconds.

In future articles I intend to divulge my secrets for chasing rainbows, discuss the tactic of timing a shoot to follow a storm to utilize the clean, clear air in a a weather systems wake, and provide tips on photographing the moon. Stay tuned.