Story and photos By Mark Matheson

Story and photos By Mark Matheson

Utah Outdoors - September 2002

IN THE SUMMER of 1974 Don Duff loaded his truck and headed for Utah’s West Desert. A fisheries biologist working for the BLM, Duff and his colleague, Iosh Warbttrton, were embarking on an improbable mission: they were going to look for trout in one of the driest regions in the country. And not just any trout; Duff hoped to find a remnant population of Bonneville cutthroats (oncorhynchus clarki utah) in the small headwater streams of the Deep Creek Mountains.

The prospects for success weren't good. A decade earlier a major Utah DWR publication had described the Bonneville cutthroat as "probably extinct."

Like almost all other subspecies of cutthroat, the Bonneville had suffered a catastrophic decline in the first century of white settlement. Factors contributing to this decline cluded the diversion and dewatering of streams, overgrazing and the introduction of exotic fish species that hybridized or competed with native trout.

In the 19th century, the Bonneville cutthroat had been abundant, even at low elevations. In Utah Lake these trout grew to perhaps 40 pounds and supported a commercial fishery. In 1864, a single haul of the net produced 3,500 pounds of trout. But, as with Panguitch Lake to the south, the indigenous trout of Utah Lake became extinct - the last recorded native cutthroat was caught there in 1933.

So Duff was facing long odds in the summer of '74 as he broke his way up a Deep Creek stream overgrown with brambles and wild roses. Surveying with hook and line, he soon began to catch fish, but disappointingly they were rainbow trout. Even this remote stream had been affected by a widespread mentality that led to the stocking of exotic fish throughout the West.

But as he continued upstream Duff began to find rainbows that appeared to show cutthroat influence, and his hopes rose. Perhaps in the upper reaches of the stream there might be Bonneville cutthroats that had escaped hybridization. When he passed a rocky fall several miles into the canyon, Duff began to catch fish that appeared to be pure cutthroat, which were later proven so through scientific testing. The falls had served as a barrier to the upstream progress of the rainbows, and Duff had established that the strain of native deep Creek trout - which had run up the range's streams from Lake Bonneville thousands of years before - still survived.

Duff's discovery was a dramatic moment in one of the most important Western conservation stories of our time: the intervention to half the decline of native cutthroat trout and to bring them back to relative abundance. Over the past 35 years, dedicated people in the public land and wildlife agencies have been working hard to accomplish this goal.

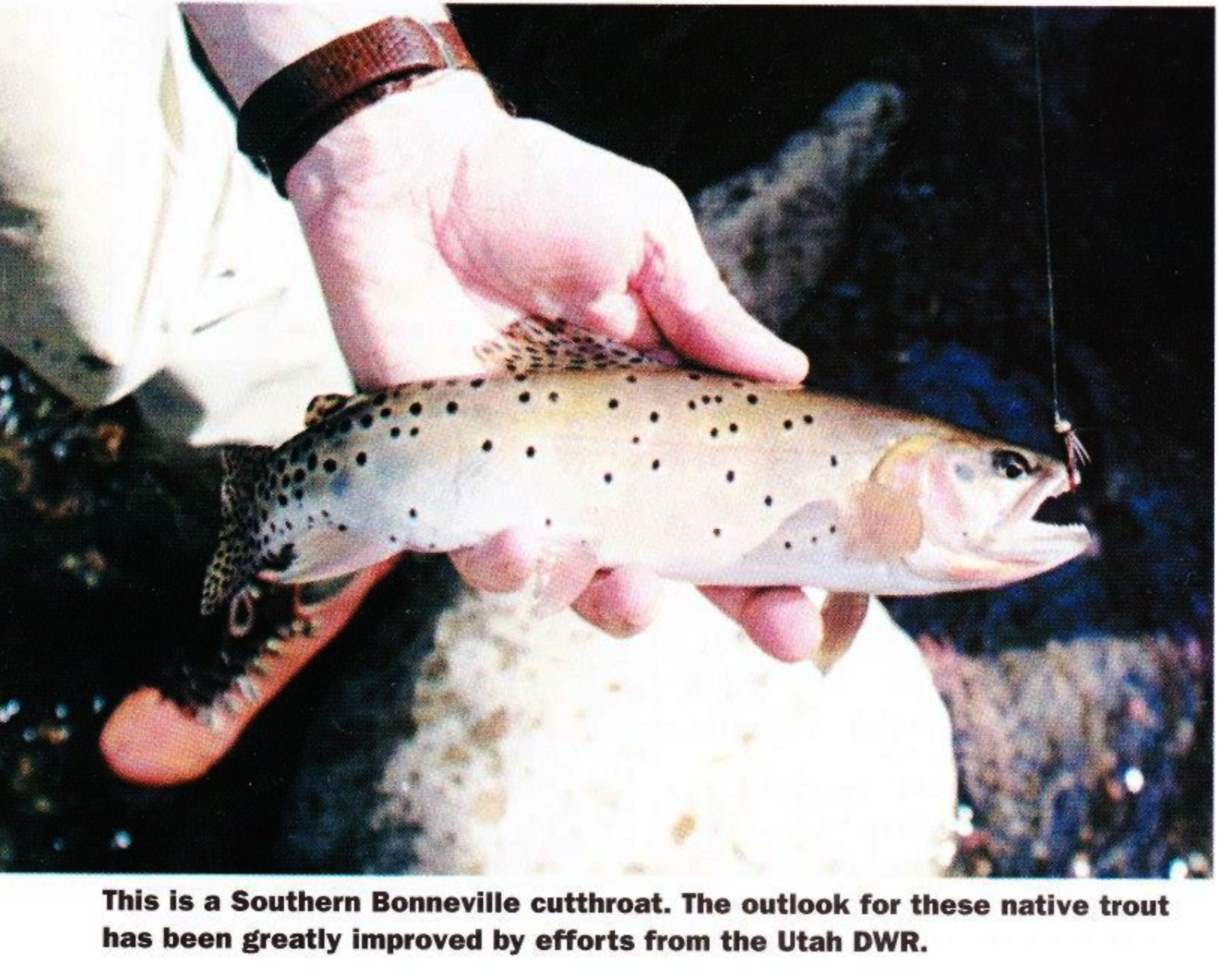

In the Southern Bonneville Basin, for instance the outlook for native trout has been greatly improved by the work of Dale Hepworth and his colleagues at the DWR's Cedar City office. A statistic helps to highlight their success. In 1977 southern Bonnevillle cutthroat occupied less than five stream miles, but in 1995 they could be found in more than 35 miles of stream with another 50 miles available for existing populations to expand. Manning Meadow Reservoir has also been established as a brood stock lake for the Southern Bonnevilles.

In the Southern Bonneville Basin, for instance the outlook for native trout has been greatly improved by the work of Dale Hepworth and his colleagues at the DWR's Cedar City office. A statistic helps to highlight their success. In 1977 southern Bonnevillle cutthroat occupied less than five stream miles, but in 1995 they could be found in more than 35 miles of stream with another 50 miles available for existing populations to expand. Manning Meadow Reservoir has also been established as a brood stock lake for the Southern Bonnevilles.

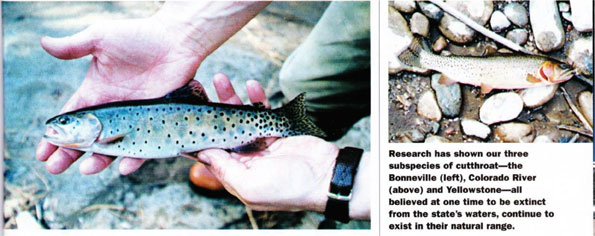

Hepworih has as well been active in restoring the Colorado River cutthroat to its natural range in southern Utah. More brilliantly colored than the Bonneville, this is the native trout in the Green and Colorado River system. Like the Bonneville, it suffered a precipitous decline, but a few small remnant populations have been discovered, including in the headwaters of the Escalante River.

Hepworth has established Dougherty Basin Lake on Boulder Mountain as a brood stock reservoir for the Colorado River cutthroat, and he reports that egg takes this year from both Douherty and Manning Meadow have been excellent. Small populations of the Colorado River cutthroat have also been found in the Uinta Mountains and on the Wasatch Plateau.

The third and final subspecies native to Utah, the Yellowstone cutthroat, was known to occur in the Raft River system in the extreme northwest corner of the state. This is the only portion of the Snake River drainage (where the Yellow stone cutthroat is native above Shoshone Falls) to fall within Utah’s boundaries. Pioneer journals indicate that the trout existed in Utah, but until very recently no Yellowstone cutthroats were thought to survive in the Raft Rivers.

But over the past two years Paul Thompson at the DWR has done extensive field surveys and has found a few relict populations in the region’s tiny streams. This is a great discovery, since it means that Utah’s native trout fauna is actually intact; the three subspecies of cutthroat, all believed at one time or another to be extinct from the state's waters, continue to exist here in their natural range.

Many of our native trout populations remain tenuous, however, and recovery efforts must continue to be vigilant. Drought, illegal stocking of exotic species, wildfires, and whirling disease are among the threats these trout continue to face. They are wonderful sport fish, which ought to be angled for (where legal) on a catch-and-release basis. Beautiful and still all too rare, these native trout are irreplaceable, the authentic jewels of our high mountain lakes and streams.

Don Duff is nearing retirement now, almost 30 years on from his discovery of native trout in the Deep Creeks. This past winter the Native Utah Cutthroat Trout Association awarded him the inaugural ”Lifetime Achievement Award.” Today, the Snake Valley Bonnevilles have been restored to numerous Deep Creek streams, and the recovery effort is ongoing.

Duff is a modest man, but he speaks with a quiet sense of achievement about the Deep Creek trout, which he and others have brought from the verge of extinction to an expanded and stable range. The wider effort to save Utah’s native trout and restore them to their original waters has indeed been a remarkable achievement, and it is a continuing project that deserves our committed support and participation.