Hiking Coyote Gulch

(See our updated 2024 guild to hiking/backpacking Coyote Gulch.)

By Courtney Humiston

After stuffing my sleeping bag and rolling up the pad, I climbed out of my tent and surveyed the land in the early dawn. Patches of sagebrush struggle out of the sandy soil and red sandstone cliffs rise on the horizon. As a stranger to the desert, I thought it seemed barren, desolate and uninhabitable. It contrasts sharply with the fond memories I have of canoeing in one of Minnesota’s 10,000 lakes, swimming in the Mississippi River, or climbing trees in the forest behind my home.

After stuffing my sleeping bag and rolling up the pad, I climbed out of my tent and surveyed the land in the early dawn. Patches of sagebrush struggle out of the sandy soil and red sandstone cliffs rise on the horizon. As a stranger to the desert, I thought it seemed barren, desolate and uninhabitable. It contrasts sharply with the fond memories I have of canoeing in one of Minnesota’s 10,000 lakes, swimming in the Mississippi River, or climbing trees in the forest behind my home.

But the desert’s splendor can be deceiving, as I discovered on a recent visit to Coyote Gulch, a side canyon of the lower Escalante River famous for its sandstone cliffs, natural arches, and waterfalls. I arrived at the trailhead above the gulch as part of a group from Brigham Young University. As we began the traverse across the solid rock, following the cairns which marked the way down into the steep walled canyon, I asked my professorÑa Utah nativeÑ"Is this what you are talking about when you say that you love the desert?"

"Well, yes," he responded in his brisk but friendly manner. He had been unable to convince me in the classroom that the desert was a beautiful place, and I still had my doubts. We had been hiking all morning across slick rock surrounded by nothing but dry brush and dark, red sand, and my water supply suddenly seemed insufficient. Even in November, the early afternoon sun was warm and causing my back to sweat under my heavy pack. By the time I felt thirsty, I knew I was already dehydrated.

Our rocky traverse suddenly ended when we reached the edge of a cliff and the earth split open at our feet, revealing the wide canyon created by the Escalante River. Cliffs of red and orange sandstone streaked with black and white traces of extinct waterfalls rose high on both sides. Looking out to the northeast I spotted Stevens ArchÑthe first and grandest of the archesÑsurrounded by massive walls of red rock and pure blue sky.

To begin our steep descent into the canyon, we carefully lowered our packs down a 20-foot rock face and then squeezed our way through a narrow cleft appropriately named "Crack in the Wall." After gearing back up, we scrambled down the sandy trail into the canyon. Once we reached the bottom, we set up camp by Coyote Creek, a shallow runoff that joins the Escalante River less than half a mile downstream from where we were. The creek, which flows year-round, is fed by natural springs along the way. The sound of running water was comforting and made me feel more at home.

The next morning we began our six-mile roundtrip hike that would pass two arches, a natural bridge and three waterfalls. The creek, although shallow, had to be crossed many times and ultimately soaked our feet. Unlike the dry rocky desert we had crossed that morning, vegetation thrives along this area. Small purple flowers and snake grass grows along the sides of the creek, and farther away deciduous trees were beginning to scatter their colorful leaves on the damp, sandy earth. Delicate maidenhair ferns cascade down the sides of the cliffs, nourished by water seeping from the rock.

The second arch we encountered was Cliff Arch. The arch itself rises high on the North side of the canyon. Resembling the handle of a teacup, it juts out of the natural canyon wall. I sat down on a log next to a pond at the bottom of a beautiful waterfall and gazed up at the arch. How these bridges of stone form is still somewhat of a mystery to geologists. What they do know is that like other formations caused by erosion, they are the result of thousands of years of wind and water eating away at the softer parts of the rock. What they can’t figure out is why the entire rock face doesn’t collapse during the formation process.

We followed the river for about a mile when Coyote Natural Bridge came into view. Cottonwood trees gather like tourists around the base of the arch. The trail passes under it, so it is possible to get very close to this somewhat smaller arch. Perhaps its most unique feature is the light, almost white color of the sandstone, contrasting with the surrounding orange and red sandstone.

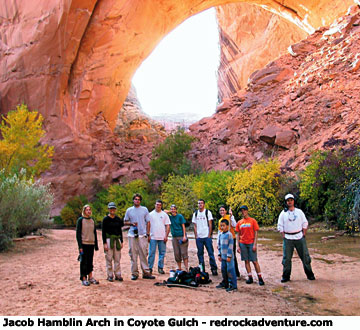

Jacob Hamblin Arch was the last arch we were to see for the day. Coming around the bend in the river and seeing this massive, yet elegant red and orange arch sweeping over the river is truly breath taking. It was worth the long hike and the muddy shoes to see this beautiful, unique formation. We rested on the large sandy banks and filled our water bottles from a clear, cold stream dripping from an overhang on one of the cliff walls.

By the time we got back to camp, the quiet solitude of twilight had begun to settle in the canyon. The bluish green flames of our classmates’ stoves gleamed in the settling darkness. After removing my wet shoes and shaking the sand out of my socks, I rinsed my face in the chill water of the nearby stream. I looked up at the cliff rising on the other side of the water, tinted with the last light of the setting sun. Reflecting on the diversity of that day’s hike, I began to understand what it was that my professor loved about the desert.

Getting there

The town of Escalante is about 275 miles due south of Salt Lake City. From Torrey, travel south and west on U-12 about 65 miles. Once in town, travel five miles southeast along U-12 until you reach Hole-in-the-Rock Road, the trailhead. Follow this road south to one of three trailheads that provide access to Coyote Gulch. The Redwell Trailhead is 31 miles from U-12. This route, which is about 28 miles round trip, requires some rock climbing ability as the descent into the canyon is very steep. Hurricane Wash Trailhead is 34 miles from U-12; the hike to the Escalante River and back is 26 miles. We chose to take the Coyote Canyon Trailhead, which is about a 16-mile round-trip. At 35 miles from U-12 is a junction with the Forty Mile Ridge Road. The trailhead is another seven-mile drive from the junction, the last two of which are through deep sand and not recommended for low clearance vehicles. From the parking area, a two-mile hike drops 700 feet in elevation to Lower Coyote Gulch. The trail ends after half a mile, and is marked by cairns.

Copyright Dave Webb