By Golden Webb

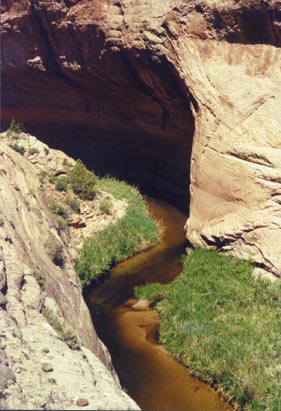

The vertical canyon walls before me pulled together and formed a constricted, twisting stone corridor that pinched out of sight around a curve. I could see that the glassy flow of the stream purling around my legs, so cold that my bones were beginning to ache, backed up behind huge boulders caught in the canyon's maw and formed a series of descending pools and cascades of indeterminate depth. Above me the upper rim of the eastern wall glowed red in the light of the setting sun; the day was dying, and soon darkness would replace the soft light, cold the warmth my body so desperately needed. A slowly spreading wave of cold, blunted by numbness, began to creep up through my innards, and a cool breeze unleashed by twilight triggered a violent shivering. I stood there in the stream at the mouth of the narrows, body tremulating, light slipping inexorably away, faced with a difficult decision.

The damp topo-map in my pack showed a possible digression up a draw on the west slope. It would involve a friction climb up the cleft and then a route-finding traverse over the swales, folds, and humps of the uplands, dropping eventually back down to the stream. But to be caught in the uplands in the dark, surrounded on all sides by sheer drop-offs, would be suicide. The other option was to somehow force my cold racked body into those deep black pools and swim the demesne of the narrows while there was still some sunlight, and therefore solar heat, to warm my body afterwards. Both options meant uncertainty, discomfort and possible injury.

The day had begun magically enough, as all days do in Escalante country, with giddy expectation rather then portent or premonition. I had camped the night before next to Highway 12 on the hogsback ridge just southwest of the beautiful hamlet of Boulder. As the day dawned I emerged from my bag like the Children of Men emerging from the rocks at the Dawning of the Age of the Sun on Led Zeppelin's Houses of the Holy - furtively, blinking, cautious, gazing about in wonder at a bright, magical new world. Stretching the kinks out in the cold, bracing morning air, I watered some blackbrush and had a look around. The clear, gelid air afforded expansive views on all sides.

To the east, screened by the glare of the rising sun, swelled the exposed naked rock and hoodoo-stone of the Circle Cliffs and Waterpocket Fold, their corroded knobs framed by the laccolithic cones of the Henry Mountains.

Swinging in a wide arc to the north was the southern escarpment of the Aquarius Plateau, it's expansive hide weaved with vast copses of aspen and pine, its gray scarps still streaked white with snow. To the west, in a huge bowl between the Plateau and the Table Cliffs, were the canyons of Calf Creek, Sand Creek, Death Hollow, and Pine Creek, a rolling table-land of sage, juniper, and pinyon split by gorges of hoary, shining sandstone dropping declivitously to cool green streams. Directly below me to the south I could see the cottonwoods of Dry Hollow, a small artery of Boulder Creek, my destination for this particular foray. I planned a day hike, a loop trip, hiking down Boulder Creek and up the Escalante to the road, and then up the road back to my car.

It was time to start. I threw some essentials into my pack, locked my car, and dropped into Dry Hollow. The descent was easy enough, a friction walk on the white Navajo Sandstone. Volcanic boulders clung to the sloping stone as if held there magnetically. The canyon bottom was still trying to shake itself out of a winter-induced comma: The stream banks were choked with stiff, lethargic stands of tamarisk and willow, and it was a real struggle to fight my way through. In a couple months these gray, skeletal snags would become a charnel ground of lush vegetation, a luxurious glen festooned with every shade of green imaginable. But for now they seemed to resent my intrusion and slapped and whacked at my bare legs with cruel vindictiveness. The stream itself was full and alive, it's swift spring flow slipping between volcanic boulders. Here and there it had scooped out tanks in the slickrock stream bed, green tubs with shimmering, glass-like surfaces.

The next few hours consisted of hard-core thrashes through the dead vegetation and wading through the shoals of the stream.

As the day wore on and the sun began to bake the stone I took frequent dips in some of the larger pools, the routine always the same: plunge in pool, explode to surface, thrash for the bank, and sprawl on the sloping stone of the canyon walls, sandwiched between the soothing heat of the stone on wet skin and the baking rays of the desert sun.

Three or four of these dips, followed by languid basking in the sauna-like heat on the stone, clears the mind, stretches the flesh tight over the bones, and produces a natural euphoria far more exhilarating than any drug-induced buzz.

What I hadn't figured into the equation when I planned my hike were the two enchanting side-slots that side-tracked me for three hours, precious time I should have been using to get down-canyon.

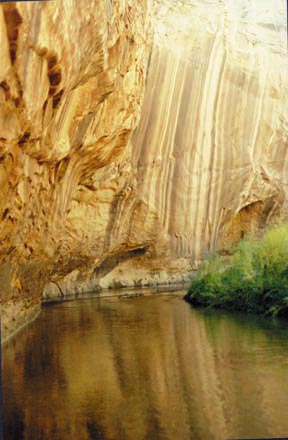

But I couldn't help myself. Through some strange alchemy the stone inside these slots seems to glow from within, radiating colors that mix with the reflected light of the invisible sun to create a kind of misty, water-color wash of light.

The rock seems flushed, organic, as if you could press your lips against it and feel not cold, hard stone but warmth, yielding softness, as if you could bite out a mouthful and make it bleed. But soon it was my blood being shed as I jammed and chimneyed through the slots, the whorls of skin on my knees, shins and elbows sanded away whenever I scraped against the grain of their seemingly smooth, water polished walls. The pain was worth it, however, the scrapes and bruises a small price to pay for entrance into these scalloped, rippling fissures.

And so that's how I found myself at the end of the day standing calf-deep in snow-melt gazing into the maw of the narrows of Boulder Creek, dazed, confused, and hypothermic. As I looked up at the eastern rim of the canyon I saw the orange strip of sunset glow fade by degrees and finally flame out. Something registered in my sun-cured brain and I realized it was time to make a decision.

Into the abyss! Instead of diving in and getting it over with I chose instead to wade cautiously into the first pool, letting the water creep slowly up to my thighs, abdomen, chest, and finally neck. It was like slowly peeling a bandage off hairy flesh - in a word, masochistic. Finally it was too deep to wade and I kicked out and went under, floating my pack along in front of me. As expected, huge volcanic chokestones had formed a series of long, pools descending deeper into the earth, perhaps deep enough to bite into the Kayenta formation.

The water was so cold and numbing that after about the fourth pool I ceased to feel physical sensations. This was strangely calming, however, and all the anxiety and fear of a few moments before was washed away by the currents. The ululating sound of water flowing over stone and the hum of the waterfalls and cascades created an elegant torque, a white hum that pealed and echoed off the walls and imparted to me a profound peace. I was enchanted, lulled and seduced by the magic, beauty, and power that was literally flowing all around me and carrying me along to . . . Nirvana, or something.

And then I was through. The walls pulled back, the stream ran out over sandy shoals, and the cliffs to the west dropped low enough to allow, miraculously, shafts of light to strike the sandy left bank. I stood in the light and sucked the warmth in through my mouth, nostrils, and even, it seemed, the pores in my skin. Slowly the light faded, and I watched as the sky overhead turned from a deep sanguine red to lavender to mallow and finally the deep blue of night. The rest of my hike would be under the light of the stars.