By Golden Webb

By Golden Webb

(Published May, 2001, Utah Outdoors magazine)

It’s just a little place, really, a rugged loop of canyon tucked away into a small cove beneath the Bears Ears and Elk Ridge. But in terms of beauty and natural wonders per square foot, few places in the Southwest can compare with Natural Bridges National Monument.

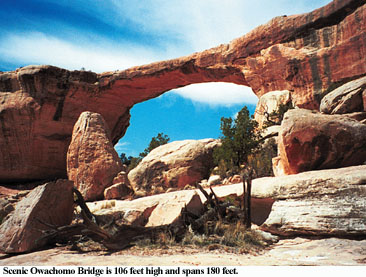

The monument’s eponymous natural bridges are among the finest examples of ancient stone architecture nature has produced. Sipapu. Kachina. Owachomo. Three massive rock spans, carved out of Permian-age Cedar Mesa sandstone by the mercurial flux of desert streams . . . stone bows stretched taut against a turquoise vault of sky. Nowhere else in the world have bridges on such a scale formed so closely to each other.

Natural Bridges is located in southeastern Utah, on a pinyon-juniper-covered mesa bisected by White Canyon and her upper tributaries, Deer, Tuwa and Armstrong canyons. Because of the monument’s beauty, ease of accessibility and user-friendly accoutrements, Natural Bridges is one of Utah’s most attractive family hiking and camping destinations. The setting is wild and woolly, but the Park Service has done a great job of providing easily negotiable trails to the bridges and in setting up interpretive displays and placards that explain the area’s rich natural history as it unfolds to the visitor.

It hasn’t always been this way. As late as 1926, Utah’s first nationally designated park unit could be reached by horse or not at all. White Canyon lies 30 air-miles west of Blanding, the nearest town, with serried ramparts of cliff wall and forested ridge thrown up between. The high desertlands north of the San Juan and south and west of Blanding were the exclusive province of cattlemen, miners and wealthy desert “dudes” — East Coast businessmen in vests and fashionable knickers who paid top dollar to be molded in the “stern and fiery crucible of the desert,” as Zane Grey put it, with a little help from such legendary guides as John Wetherill and Zeke Johnson (who became Natural Bridges’ first ranger and custodian).

It was probably some anonymous local cowboy who first laid European eyes on the bridges, but the recorded right of discovery goes to Cass Hite, Scotty Ross, Edward Randolph and Indian Joe, who in September 1883 came up White Canyon from Dandy Crossing on the Colorado looking for gold. The prospectors named the bridges “President,” “Senator” and “Congressman” (in order of decreasing size), then promptly forgot about them.

Twenty years later, a stockman who had ranged cattle in the area, J.A. Scorup, led a Colorado River gold dredger named Horace J. Long to the bridges. The account of their trip ultimately led to a notice, “Colossal Natural Bridges of Utah,” published in National Geographic magazine in 1904. To many, the story seemed unbelievable. Three stone bridges. Clustered together. Far bigger than anything previously discovered or even imagined. This was something people had to see.

One person who saw was the English-born H.L.A. Culmer, an artist who visited the bridges in 1905 and who produced oils and beautiful prose that helped to prominently fashion the popular perception of the canyon country — a sort of fin de siecle Ed Abbey. Erosion in southern Utah, Culmer wrote,

[has]created scenes of magnificent disorder, in savage grandeur beyond description. The remnants of the land remain of impressive but fantastic wildness, mute witnesses of the powers of frenzied elements, wrecking a world. These were the powers that fashioned those monoliths that rise like lofty monuments from the southern plains; that shaped those enormous bridges in the rim rock region of San Juan… and they strewed over a region as large as an empire such bewildering spectacles of mighty shapes that Utah must always be the land sought by explorers of the strange and marvelous.

In keeping with a certain peculiar American penchant, the bridges have been assigned three different sets of names since their discovery. Scorup and Long renamed them after people they knew: “President” became, of all things, “Augusta,” after Long’s wife; “Senator” became “Caroline” for Scorup’s mother; and “Congressman” became “Edwin” for Edwin Holmes, the sponsor of their expedition.

The bridges’ present names, derived from Hopi words, were assigned by a United States Surveyor named William B. Douglas, who mapped the area in 1908. Sipapu (SEE-pah-poo) means “place of emergence,” an opening between worlds by which the Hopi believe their ancestors entered the present terrene sphere. Sipapu is the largest and the most spectacular of the Monument’s bridges. It’s considered middle-aged, older than Kachina but younger than Owachomo. Kachina (ka-CHEE-na) is named for the Hopi katsina spirits that frequently displayed lightning snake symbols on their bodies. Similar snake patterns carved by prehistoric people can be found a hundred feet south of Kachina Bridge on the west side of the canyon. Owachomo (o-WAH-cho-mo) means “Flatrock mound” and was named for an outcrop on its east side. Because Owachomo no longer straddles the streams that carved it, the bridge actually resembles an arch. What’s the difference? Bridges are formed when flowing water bores through a canyon wall. Arches are the product of frost action and seeping moisture.

The three bridges and the world famous Horse Collar Ruin can all be seen from viewpoints along or just off the monument’s loop road, but you won’t truly experience the hidden beauties of Natural Bridges unless you get away from the pavement. A series of trails drop into the canyons and wind through the pinyon-juniper forest atop the mesa. Hikes vary from easy half-hour strolls on relatively flat terrain to an all-day loop that connects White and Armstrong canyons together.

Starting at any of the bridges, the Bridges Loop takes you to all three bridges, past Horse Collar Ruin, and back across the mesa top to your starting point. The entire loop is approximately 8.2 miles long and requires about five to six hours walking time. If you don’t have enough time to do the entire loop, hiking between two of the three bridges shaves a few miles and cuts the time to 3 to 4 hours. Or you can do what a lot of people do and simply drive to the three major trailheads located almost on top of each of the bridges. Ladders and rails have been placed to help you over the steep spots.

Any of the various combinations of trails into and out of the canyons should be considered strenuous, requiring ascents and descents of up to 500 vertical feet. Since monument elevations range from 6,000 to 6,500 feet above sea level, you’ll be a little short of breath getting back to the rim. Keep in mind that hiking the trails during winter can be hazardous due to accumulations of ice and snow, especially the sections entering or exiting the canyon at Sipapu and Kachina bridges.

If you go

Distance from Salt Lake City: 315 miles

Getting there: Natural Bridges National Monument is located in southeastern Utah just off Hwy. 95, about 40 miles west of Blanding and 50 miles east of Lake Powell’s Hite Marina.

Best time: As with most places in southern Utah, the best time to explore Natural Bridges is in the spring or fall, though visiting the monument in the dead of winter or the peak summer months translates into more solitude. Whatever the season, bring varied clothing layers. Mild winter days make hiking in light clothing possible, but at 6,505 feet above sea level, below zero temperatures are not unusual in the colder months. Rain is possible at any time, especially in spring and late summer, so also bring along some rain gear.

Camping: The monument’s 13-site campground is open year-round but is not cleared of snow in the winter. The camping fee is $10 per night. No reservations are accepted and there’s no group site available. Fires are permitted in the fire pits, but no wood gathering is allowed inside the monument. Vehicles over 26 feet long are not allowed inside the campground. The sites typically fill by early afternoon from March through October, but rangers at the visitor center can give directions to alternate camping areas located nearby.

Entrance fees: $6 per vehicle, $3 per person (bicycle, motorcycle or walk-in). National Parks, Golden Eagle, Golden Age and Golden Access passes are accepted and available for sale. Annual passes for Natural Bridges, Canyonlands, Arches and Hovenweep are also accepted and available for $25.

Contact: Natural Bridges National Monument, HC 60 Box 1, Lake Powell, UT 84533; (435) 692-1234; nabrinfo@nps.gov (for general information).

Maps: Trails Illustrated Manti-La Sal National Forest Map, and USGS Moss Back Butte and Kane Gulch Quads.

Guidebooks: On area history: C. Gregory Crampton, Standing Up Country: The Canyon Lands of Utah and Arizona, University of Utah Press; Jared Farmer, Glen Canyon Dammed: Inventing Lake Powell & the Canyon Country, The University of Arizona Press. On hiking: David Day, Utah’s Favorite Hiking Trails, Rincon Publishing Company; Dave Hall, Hiking Utah, Falcon Press Publishing Company.