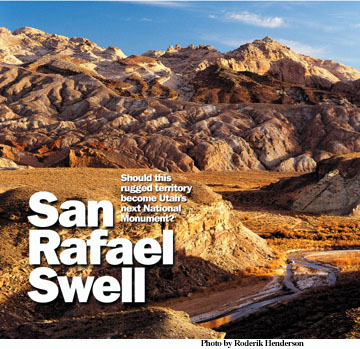

The Swell will not be designated a national monument – at least not in the near future – because Utah Governor Mike Leavitt is honoring his pledge to respect the wishes of local residents. Leavitt pushed hard for the monument and won support from a broad range of interested groups, but the issue was shot down in a non-binding vote by locals afraid the disignation would allow the federal government to shut down backcountry travel.

But the monument idea is far from dead. The Swell is one of Utah's treasures and supporters will continue to push for some kind of increased status and protection. Below is our writer's take:

The Upper Muddy and Ernest Shirley

By Golden Webb

(Published April, 2002, in Utah Outdoors magazine)

Near Fremont Junction on Interstate 70, an unmarked dirt road spears south into the desert. I'm sitting on the shoulder of the highway with a topo map draped over the steering wheel, tracing my route through a tough, lonely, lovely land. I plan to go far today-south to Segers Hole on the backside of the Reef, west to the Mussentuchit Badlands, then southwest through Cathedral Valley to the welcoming black tar of U-24. I twist a can of Coke off the six-pack, pop the tab, and have a sip to fortify myself for the journey ahead. Then I swing onto the dirt.

In the San Rafael Swell, desert doubletrack comes in three varieties: bad, abominable, and bug spit. The road I'm driving south on is merely bad. Sandy, dusty, rutty, off-camber-and I've barely gone half a mile. There was rain out of Salina and snow over Wasatch Pass, but down here the sky's blue-the storm is staying west over the mountains. The February sun through the windshield is hot on my forearms and face; when I roll down the window, red powdery dust swirls inside. No matter. On a continuum of smells that make me happy, the clay scent of desert dust ranks somewhere between wet sage and Victoria's Secret lotion effervescing off a warm woman's skin. The dust even tastes good. Like salt and tequila, a mouthful of red-dog dust makes the cola go down smooth-desert Schlitz for Mormons. I take another sip.

At 20 miles per hour, my Suzuki's rattling like a diamondback: slow down. The road snakes off across an unlikely wasteland, following an unlikely route through and around the headwater gullies of Upper Muddy Creek. The Upper Muddy lies on the hinterlands of the second largest swath of undeveloped BLM land in Utah, which in turn bisects the midriff of what was, until a few decades ago, one of the 10 largest desert roadless areas in the nation: the great uplift called the San Rafael Swell. From my vantage on the Upper Muddy I can see the western flank of the Swell as it rises to the horizon: a general upslinging of the land toward Sinbad and the naked rock of Hondu Country, with nothing whatever to suggest the labyrinthine gulf on the other side.

Farther up and farther in. I jounce along, banging against the door like a bucket in a well. As the landscape plays out before my eyes, it begins to dawn on me that this isn't really a place where hug-a-tree homilies apply. The Upper Muddy is like the Canyon Country's crazy aunt, locked away in a back room of the Colorado Plateau, with mile after mile of burnt-out hardpan and rotten talus slope. Brooding basalt-capped mountains. Serrated fins of volcanic rock that radiate across the land for miles, like some Mesozoic Maginot Line (to keep us out? to keep something in?). Disarticulated horse skeletons. Hidden valleys and poison gulches. Glittering beds of selenite. Grendel, Gollum, Sauron, Satan, various and sundry Fremont Indian devils, and the occasional moon-faced cow.

The first Mormon settler to encounter these rawboned badlands probably took off his hat, sighed, and spat in the dirt. Early ranchers said of the area: "One must not touch it." More than just about any other place in Utah, you'd expect Mussentuchit, the Upper Muddy, and other remote regions of the San Rafael Swell to be de facto wilderness, but they aren't. Not anymore. The frontal assault of I-70 across the heart of the Swell made sure of that. And as if to prove that this has never been the Heart of Darkness anyway, I pass the following: a Nissan SUV full of smiling mountain bikers; an old Indian woman with a canvas bag swatting at ricegrass with a switch (collecting seeds?); and a couple in a red Ford truck with the windows rolled down, towing a horse-trailer. As I pass by I wave at each in turn. Everybody in the Nissan waves back, the Indian woman never looks up, and the couple in the Ford gives me a long look that seems to say, "Where are you going, idiot?"

It's pretty heavy traffic for a dirt road in the middle of nowhere-on a Monday evening in the dead of winter. People have generally stayed away from the Swell in droves, preferring instead the pavement and officially designated parking spots of Arches, Canyonlands, and Capitol Reef. But the winds of change are blowing like a nor'wester off The Wedge. Gov. Mike Leavitt recently asked the Bush Administration to set aside 620,000 acres on the Swell as a national monument. What its exact boundaries would be, which land-use rules would apply where, and whether Robert Redford and Terry Tempest Williams would be leading a chorus of "Cumbayah" at the dedication ceremony, he didn't say. In a refreshing twist, the group least surprised by Leavitt's proposal was the Emery County Commission, who'd been closely involved in what Leavitt described as the "seven years of intense negotiation" that brought the monument proposal to the table. This in contradistinction to Bill "Grand Staircase-Escalante" Clinton, whose 1996 end run on 1.7 million acres of the Paria, Escalante and Kaiparowitz left many southern Utahns feeling like a jalopy in the blind spot of a drifting Federal asphalt truck: irrelevant.

Was a real nice place...

The day before I'd been in Hanksville, trying to get a feeling for what the southern Utah "street" thought of the governor's monument idea. I should have worn a raincoat. Make inquiries about national monuments, SUWA, wilderness study areas, or the BLM in an archetypal desert town like Hanksville, and you'll encounter descriptions of government tyranny not heard since Solzhenitsyn's "The Gulag Archipelago." "If they could, they'd push us right off the land" is the constant refrain. But everything these Hanksville-ites have to say on the subject has a special moral weight to it, for one simple reason: this stuff really impacts their lives.

For people on the Wasatch Front, the "War of the Wildernesses" is basically academic. On the one side are the chattering environmentalists, who seem uncomfortable with the notion of honest people making an honest living off the land. On the other are the good ol' boys of the ATV lobby, who've never seen a bentonite hill they didn't want to do a wheelie over. In the middle are people who listen to the opposing arguments of both sides and think, "Good idea."

The residents of towns like Hanksville, Escalante, and Kanab don't have that luxury of distance. And past experience has taught them to be wary of what the latest talking head is saying about the "management" of their backyards. But they're not flat-earth advocates; just underneath those defensive quills there's a basic will to please, to do the right thing. They just want to be left alone to do it.

Ernie will tell you.

"I think it's bullshit," said Ernest Shirley the first time we met. He was leaning on the Formica countertop in his rock shop, an old wrinkly relic of a man in Big Mac overalls surrounded by old relics resurrected from the dust: dinosaur bones, petrified wood, potsherds, agate, obsidian, arrowheads, sliced and polished coprolytes and various other esoteric (and possibly radioactive) geologic oddments. Ernest is 83. He retired a long time ago, but continues to run the shop for the love of it-love of rocks, love of strange "artifacts"-a word Ernie used a number of times as if it had special savor. "Ernie's got this giant allosaur bone in the back of his shop somewhere," Shirley's friend Barbara Ekker told me. "He came West with the CCC, ended up in Hanksville somehow, and never left."

"I come here because there wasn't a lot of people," said Shirley, making an expansive gesture that seemed to include all the miles and miles of wild country that surrounds Hanksville like the Pacific surrounds an atoll. "Was a real nice place then. Used to be the Ekkers and Johnsons and Welseys, then the Alveys and Whipples come along too. That was back during the War."

An angry light came into his eyes.

"During World War II we had two enemies: Communism and Fascism." He stabbed the air in front of my face with his index finger. "But today we got worse fascism than Hitler in this country. It's got so I got to go 70 miles just to ask some idiot if I can build a fence. The government made it so there's not enough land to make a living on. Not enough to support people on the land now. And you never see a county commissioner after they're elected; of course you never see a federal man at all."

He'd already told me what he thought of the new monument, so I tried a different tack: What did he think about SUWA's crusade to have much of the Swell designated as wilderness?

"Those people?" he said. "They complain about if a guy want to run cattle, if a guy want to cut some firewood, fight everything there is. All of us is environmentalist to a certain extent, but you don't make yourself look good, and you're not helping the country either when you try and push people off their land."

Standing next to Ernest Shirley made me feel like the poseur I am. Had I ever blazed roads into the howling wilderness, or built bridges over muddy desert rivers-bridges that still stand today? Ernie had. Loaded a giant dinosaur bone into a wheelbarrow, rolled it for miles over rocky desert terrain, lowered it down a sheer cliff, and got it home intact-one of the greatest fossil specimens ever found? Ernie had. Mined the uranium off Temple Mountain that went to the first atomic bomb? Ernie had. Grubbed for hours in the hard alkali soils of the Morrison and Mancos Shale looking for "artifacts," fumbling and stroking and prodding and poking, engaging in foreplay with the very desert earth itself? Terry Tempest Williams thinks she has, but I don't think there's ever been a greater Cassanova of desert soils than Ernest Shirley.

So when Ernie says he doesn't want a new monument in his backyard-in a place where he's toiled and shed blood, a place he knows better than any SUWA apparatchik or county commissioner or coifed politician will ever know because they've never worked there, don't live there, won't die or be buried there-does anybody listen? I don't think anyone outside of Hanksville has ever listened to Ernie. And I don't think anyone ever will.

Routes to nowhere

Farther up and farther in. I climb the pass between Cedar and East Cedar Mountains, intersect a faint trackway coming in on the left, and follow it southeast. I could have gone west on another track, or straight south, or southwest, or looped around north again: different paths following different routes to nowhere.

Rounding a corner I see a tumbleweed in my path. When I'm in the desert my instincts become preternatural, like an Israeli commando in the Negev. This time it's no different. I gun across a sandy wash, roll over a whaleback, lean through a hairpin curve, and speed off like a Robbers Roost bandito toward the ominous black belly of the Moroni Slopes-the tumbleweed dragging along somewhere under my chassis.

And then, suddenly, the Edge of the World: just another place in the Swell, like a million others, that's so damn beautiful and otherworldly you can't even wrap your mind around it. The sun is sinking low in the sky, the slanting light warm on the land. I step out onto slickrock and walk to the edge, to a spit of sandstone high above Segers Hole, and look out over the superlative chasm of the Lower Muddy Creek Gorge where it cuts through the wall of the Southern Reef.

The dying sunlight moves in pulses across the sandstone. Way off in the distance Temple Mountain glows like an ember, like a shining beacon atop its battlement in the heights of the Reef. I feel like Moses, looking at God's face on the mountain. But Moses lived for 40 days and 40 nights on Horeb-I'm just an interloper here. This is Ernie's Country. I get back in the Suzuki and fire her up. I reach down and twist a warm Coke off the six-pack, take a sip. I put her in gear (I'll be shifting between second and first for the next 70 miles) and shine my high-beams out onto the gathering night. Then I swing onto the dirt and drive south on a road some miner or rancher built before I was born.

Should they make a new monument in the San Rafael Swell? I think they should-no matter what Ernest Shirley says. Just so long as they leave it the way it is, and don't push anyone off the land. And let Ernie collect his rocks, and the Eckers run their cattle, and the dirt-pick miners search for their radioactive gold. Call it the Anti-Grand Staircase-Escalante. Dedicate it, and let Ernie give a speech. Then give it right back to the people who know this land best-we know who they are. They've been living and working in this tough, lonely, lovely land for a long time.

They know what to do with it.