Floating Desolation Canyon

By

Peter Francis Tassoni, BLM River Ranger

By

Peter Francis Tassoni, BLM River Ranger

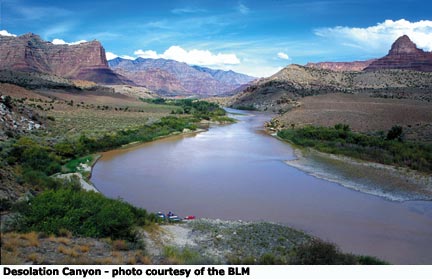

The Green River flows out of Split Mountain and meanders its way through the Uinta Basin before plunging into Desolation and Gray canyons in central Utah. It cuts through some of the youngest geological formations in Utah: rocks etched with fossils; canyon walls splashed with red, gray, black and white hues; arches, pinnacles and erosion-formed sculptures only nature can produce. These canyon gems of Utah river running were aptly named by members of Major John Powell's exploratory expeditions in 1869 and 1871.

This remote area, called Deso by veteran river runners, is now a major river destination for novices and old-timers alike. People return year after year to experience its fun white-water and spectacular scenery, along with its dramatic weather and the persistent insects.

The BLM is charged with managing these canyons and the river recreation they draw. In 1979, the BLM created a lottery permit system to minimize crowding, adopted river user regulations to protect the wilderness aspects of the river corridor and integrated a pro-active river ranger patrol program to restore the canyon to a primitive, if not pristine, condition. After two decades of persistent work and educational efforts, the river's beautiful white sand beaches, shaded by sentinels of mature cottonwood trees, are devoid of trash, waste material and campfire scars.

Abundant Fremont rock art and granary structures dot the landscape in these remote canyons. Signs of intrusion by the cowboy and outlaw cultures add interest and have been preserved for historical reasons.

Best of all, this section of the Green River is one of the easier destination corridors for a private party to receive a launch permit. "Any canceled commercial allocation is put back into the kitty and private parties calling in for cancellations or open launch dates can pick up that canceled commercial launch," explains Pam Swanson, the river ranger responsible for the permit system. "We also charge a unique "no-show" fee to commercial outfitters that prevents them from over-booking the permit system. This keeps the canyon relatively available to everyone."

High-use season runs from May 15-August 15 of each calendar year, with six launches per day allowed; only two launches per day are allowed during the low use-season. The high use season generally has higher water levels, warmer temperatures and more folks on the river while low use season is splendid for slower trips filled with solitude.

"Historically, twice as many private parties go down the river than commercial outfitters. Total use of Deso is around 6,000 passengers spending about 35,000 user days on the river," adds Swanson.

Wild

and scenic

Wild

and scenic

Desolation canyon, with all its wilderness properties, is still not protected with either Wild and Scenic destination or Wilderness legislation. Deso's preservation as a national priority is on a dim back burner. The BLM did remove most of the livestock grazing allocations along the river corridor 12 years ago and then eliminated the feral bovines trapped on the river bottoms.

"With the removal of livestock from the riparian zone, willow and cottonwood survival increased. In the past decade there has been a documented displacement of tamarisk by the native willows," boasts Dennis Willis, the recreation planner supervising the Desolation river program. "Apparently, the cows ate the young willow shoots and avoided the tamarisk, creating a competitive advantage for the exotic salt cedar. Now willow predominates throughout the riparian zones."

But the canyons are far from being restored to their indigenous state. The newest exotic threats to Deso are Russian Olive, Russian Knapweed and Tall White Top and removal of these exotics is brutal physical work accomplished mostly by impassioned volunteers.

"Deso retains the largest range of resident fauna in the Colorado drainage," said Willis. "A small herd of wild horses roams unmolested in the upper end of Desolation Canyon. The Utes have reintroduced desert bighorn and Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, as has the BLM. The Utes also have a healthy population of moose and bison in the reservation's Hill Creek extension. Only wolves and grizzlies are missing from the prehistoric fauna spectrum."

"The humpback chub, bonytail chub, razorback sucker and Colorado squawfish evolved in isolation when the Colorado Plateau uplifted and are specifically adapted to the pre-dam drainage with its fluctuating stream flows, muddy waters and high summer-time water temperatures. Changes in water quality, reduction in spawning areas and food source competition from exotics like bass, trout, minnows, carp and catfish are negatively affecting their populations," lamented Willis. "These are incredibly unique fish. But there are regulations in place to help their survival. Anglers are required to release these fish unharmed when accidentally caught and river runners cannot use soaps in the sensitive spawning areas, which include all the perennial tributaries of Deso. Consequently, survival prospects are starting to look less grim."

In a business venture for tribal members, the Utes experimented with a riverside lodge on the old McPherson ranch, selling hot showers, lodging and ice cream to boaters. But the contemporary 70s-style motel has become dilapidated from neglect. I think river runners would pay a nominal fee to hike and camp on Ute tribal lands if the Utes eliminated the feral bovines razing several tributary flats and restored the old historic ranch buildings at McPherson.

Conservations with a river ranger

I spent almost a decade on Western rivers as a commercial raft guide and river rat before joining the BLM. As a river ranger, I educate new and old boaters alike on the latest "Leave No Trace" river running techniques and technology. I instruct, I cajole, I commiserate, I demonstrate; I serve and protect our public lands without coercion or threat of violence. Luckily, river runners are progressive caretakers that minimize their wilderness impacts. Litter is the biggest problem on the river, not navigation. But every river runner I've met helps with the stewardship of the canyon. That shared ethic makes my job easier.

Novice Boaters

"Don't you get bored on all this flat water?" asked my friend from his kayak. "The white-water sucks."

"Rapids change with different water levels," I stated. "There's always a hole that will flip you or a rock to stick. And there's always floating hazards on any river."

"Like trees, livestock and other idiots?"

"Desolation Canyon's relatively easy rapids attract a lot of novice boaters and families. The scenery, wildlife, camping and cultural sites keep them coming back."

"But novice boaters get into trouble."

"Rarely. You need a fundamental understanding of river hydraulics, 'leave no trace' camping ethics and first aid procedures to have a successful time out here. But most new boaters have taken a course, read articles or were guests on a commercial operation. As long as each party has a viable water-craft, oars or paddles, serviceable life jackets, first aid kit, repair kit, pump, bail bucket, toilet system, firepan, food strainer and a launch permit, they can go down the river."

"What about food, water, camping gear, kitchen equipment and clothing?"

"Those are necessary but not required."

"Don't first timers get hurt a lot out here?"

"Rarely. I occasionally encounter injuries incurred by people negligently engaging in stupid activities like climbing, diving and falls. Mostly it's very experienced wilderness users practicing poor judgment, like yourself."

"Sure they're not attempts at gene pool purging?" he suggested.

"I have an obligation to assist folks in trouble no matter what the antecedent."

"Big Brother superceding individual responsibility?"

He was drifting further away.

"I rely on education and directive suggestions," I yelled.

"Same thing. It's just a softer form."

I grimaced, looking over my shoulder and scanned the tree debris floating down the river behind us. My friend was correct. I wanted people to take charge of their actions and brave the consequences. It would minimize government intervention and legal proceedings. I pulled on the oars and grabbed some slow water. A 60-foot cottonwood passed and plowed straight into the hole. It cart-wheeled once and washed out. We were next.

The Fremont Culture

"What does this mean?" she asked pointing at a sunflower pattern. It was one figure among several dozen. All were equally weird and without apparent meaning.

"Dunno," I mumbled.

The raft was tied up to sagebrush and we were standing in front of a boulder containing a panel of petroglyphs at the confluence of the Price River. The stone tool-using members of the prehistoric Fremont culture had pecked various figures in apparent haphazard confusion into the dark surface of a weathered face of sandstone. We had stopped to view the panels at Rockhouse, Flat and Rock Creek canyons previously on this patrol. "Think this is a ceremonial rite written in rock?" she asked in her Georgian accent.

"Could be. The Fremont Indians are a relatively undocumented culture. There is one page written about the Fremont for each thousand pages written by the Anasazi."

"Ancient Puebloans," corrected the volunteer.

"Correct." I shifted my oversized sunhat and itched my forehead. "Your interpretation is as valid as anyone's. Astronomical events, fertility rites, hunting legends, travel instructions, or mere graffiti have all been proposed to explain these panels."

"It must mean something. It takes a lot of time and energy to hack these figures into the rock. The Fremont survived in this canyon for over a thousand years. They must have left some wisdom hidden in these panels."

"Archeologists have found very few artifacts or middens to analyze the behavioral patterns of the Fremont. Nor are there descendants to explain Fremont oral traditions or rock art. The Fremont culture is a big mystery of the prehistoric past."

"It looks like someone chipped off some petroglyphs here."

"It could be natural erosion," I suggested. "There's a thin crack here that captures rainwater and causes the rock surface to flake off with the normal melt-freeze cycles of winter."

"Maybe, but these look like pry-bar marks to me."

Thunder clapped in the distance.

"Damn," she swore. "Here's some cowboy markings: 77 and a name."

"Those might be from early river runners, too."

She snapped off two photographs of the panel. The breeze was stiffening. We were six miles from the take-out on a trip neither one of us wanted to end. "I wonder what the Fremont's secrets to surviving over a thousand years in these canyons were while the cowboy homesteaders lasted less than 50 years?" she asked.

"Travel light and keep moving," I said. "Never take all of anything or try to change the environment to fit your comfort zones."

"It seems ironic that the cowboy culture is romanticized even with all the destruction they brought to the desert Southwest while the Native Americans were viewed as savages. Yet even the early Indians practiced communal living and resource conservation. Things our white society is just beginning to learn."

"Maybe humans are the disease of this world," I joked.

"Why did the Fremont leave?" she asked after a pause.

"I don't have those answers."

"Then what good are you, Mr. River Ranger?"

"I'm just trying to prevent folks from vandalizing these archeological sites in the hope that future scientific investigations will uncover the answers to the mysterious Fremont culture."

"I was just kidding," she said. "But I guess things disappear."

"Rock art panels have bullet hole scars, metates are missing and granaries are needlessly broken into by souvenir hunters."

"That sucks."

"I think ethics are changing but there's still a few bad apples stinking up the whole bushel for all of us."

"Sacrifice a few spots to the tourists and vandals but save the rest, right, Mr. river ranger?"

"Unfortunately."

Help needed

The BLM River Office has paid volunteer and internship opportunities available:

Contact:

BLM

125 South 600 West

Price, UT 84501

435-636-3623

Basic information

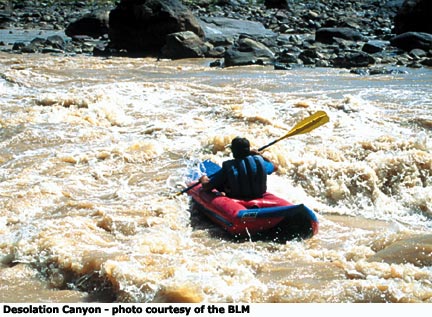

Desolation usually offers Class I-III rapids during peak season and

Class I-II most other times.

Rubber rafts are most commonly used to float the river.

Kayaks and canoes are also appropriate.

The average trip through Desolation requires 5 days but ranges from

3-9 days.

Reservations to float Desolation Canyon can be made by contacting:

BLM River Office, 435-636-3622; 125 South 600 West, Price, UT 84501.

The office takes reservation calls from 8 a.m. until noon, Monday

through Friday.

Information on river trips can be found on the Internet at: http://www.ut.blm.gov/price/index.html

There is no application fee.

Successful applicants must pay $18 per person to float Desolation.

The fee pays the administration costs of the river program. This is

a nominal amount compared to the equipment investment, driving effort

and opportunity for a high quality pristine recreation experience.

The BLM also has a complete list of licensed commercial outfitters

providing adventure trips through Desolation and Gray canyons.

Copyright Dave Webb